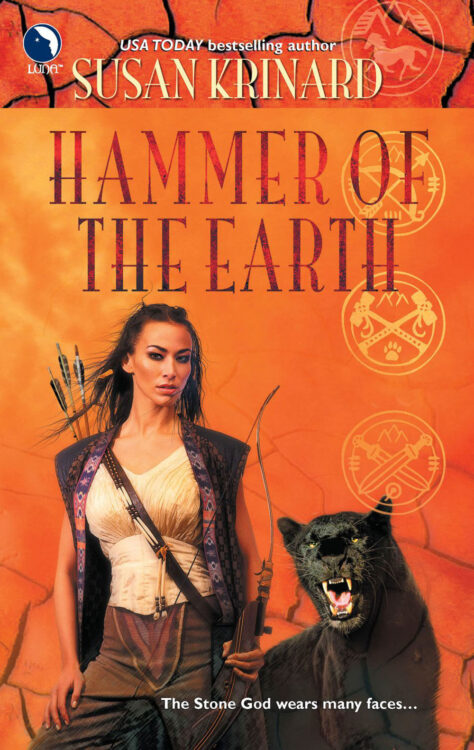

The Stone God Duology, Book 2

Hammer of the Earth

The Stone God is building in power….

Defeating an empire takes many weapons, and Rhenna and her band—including shape-shifting panther Cian—must brave unpredictable dangers, crossing vast deserts, trackless jungles and impenetrable swamps to seek the Hammer of the Earth.

Yet the Exalted Ge, who holds the Hammer in her stronghold, has set deadly traps that rise out of the Earth itself. Even if Rhenna and her companions can defeat a goddess, do they dare trust each other when the Hammer has done its work?

Meanwhile, in Karchedon, their ally Quintus must decide if working from within the Emperor’s palace will aid in the downfall of the Stone God or simply betray all he holds dear.

Despite every battle won, the power of the Stone God still stands against them. And the ultimate victory may demand the ultimate price….

Read an Excerpt

Chapter One

Karchedon

It was a prison. A luxurious prison, to be sure, furnished in royal style and adorned with every comfort a king’s son might wish. Quintus had not seen its like since he was a young boy, not even in Danae’s opulent quarters.

He thought it must be a jest, a condemned man’s last view of a life he would never have. A life he had never wanted.

Quintus sat in an ivory-inlaid chair, exhausted from a long night’s pacing. No one had come to see him since his transfer to Nikodemos’s custody. He had expected far less pleasant accommodations, where he could remind himself with every clank of chains and breath of stale air that he was Tiberian.

But he’d been spared a painful and inevitable death at the High Priest Baalshillek’s hands only to face a prospect as bitter as it was unthinkable.

He was the half-brother of Nikodemos, ruler of the Arrhidaean Empire, nephew of Alexandros the Mad. How the absent gods must be laughing.

I am Tiberian.

He slammed his twisted left hand on the chair, relishing the pain. Why had his father not told him? Why had he been allowed to grow to manhood believing that he was a true-born son of Tiberia, of the Horatii, ancient in loyalty and honor? Why had the family of Horatius Corvinus taken the terrible risk of raising the emperor’s condemned bastardson?

Quintus stared at his crippled hand. Philokrates had known. Had he been the emperor’s agent from the moment he had come to the Corvinus household until he had revealed himself as Talos and fled to the palace? Had he bribed Quintus’s adoptive father, or threatened him with a fate worse than mere conquest?

No. No bribe, for Quintus’s family had not been saved. And Nikodemos hadn’t known his half-brother lived. The only man who could answer Quintus’s questions was the one he had loved most and never dared trust again — Philokrates himself.

Quintus jumped up from the chair and resumed his fruitless pacing. It didn’t matter how he had come to be here. His future was dubious, at best. He was caught in a war between emperor and High Priest, between his two deadliest enemies. Nikodemos might exploit or discard him, depending on his usefulness — welcome him as long-lost kin or throw him into the sacrificial flames.

But that would be the high priest’s Baalshillek’s desire. No, if Quintus was to die, it would be by more common and secretive means. And if he were permitted to live…

I will never be a tool. Not his nor the rebels’, not even for my own people.

No common tool could turn in the hand of its master. But Quintus bore in his own flesh a weapon that Baalshillek greatly feared. Boldness and courage would count with Nikodemos, but Quintus must be cunning, as well, if he were to survive Baalshillek’s machinations. He couldn’t afford a moment of weakness.

His thoughts flew to Danae and the last time he’d seen her, playing the part of his hostage. She must have convinced Nikodemos of her innocence; if Quintus saw her again, it must be as if they were truly enemies.

But she might know what had become of his friends, the companions who had earned his respect and loyalty in the fight against the Stone. Rhenna of the Free People; Tahvo, shaman and healer of the far North; Cian, the shapeshifter who was neither wholly man nor beast but something of both.

Were they still in the city? Had they, too, been captured? Or were they dead by sword or evil Stonefire?

No. I will not believe it….

The door to his chambers swung open. A pair of grim young palace guards snapped to attention, spear-butts hammering the tiled floor. Two more soldiers stood behind them.

“You are to come with us,” one of the guards said.

“Where?”

“To the emperor.”

The time of judgment was here. Quintus straightened the simple chiton they had given him, adjusted the himation to cover his left arm and joined the guards. They were well disciplined, Nikodemos’s men, but they had none of the too-perfect bearing that marked the Temple Guard. They were human, unbound by the Stone. But they would kill him just as swiftly if the emperor so commanded.

The guards marched their prisoner down stone corridors decorated with frescoes of victorious battle, through several doorways and into a wide, columned anteroom. A bust of Arrhidaeos, Nikodemos’s father — and Quintus’s — stood watch at the golden double doors at the end of the antechamber. “The emperor holds court,” the guard captain said. “You will bow and hold your tongue until he addresses you.”

Quintus stared straight ahead as the doors swung open. A vast space lay ahead, echoing with whispers and the shuffling of sandaled feet. War banners hung on the walls, and gold glittered on slender necks and bare arms. Braziers lit the windowless room, carrying the fragrance of rare incense. The voices of flute and lyre mingled in sensual flirtation.

Nikodemos sat on his golden throne like the king he was, thickly muscled arms draped on the lion-faced arm-rests. Tumbled hair almost covered the plain circlet on his brow. He needed no elaborate headdress to proclaim his position.

His most trusted advisers, a dozen older men and officers near his own age — commanders who had led Nikodemos’s troops to victory again and again — stood at the foot of the dais. Danae sat on a stool at his knee. She wore a sheer chiton that left her right shoulder bare, and a fall of delicate golden bells spilled from her neck into the shadow between her breasts. Her hair was arranged in delicate flaxen ringlets. Her gaze was cool, sweeping over Quintus as if he didn’t exist.

The other courtiers — the remainder of Nikodemos’s favored Hetairoi, or Companions — followed her example. They laughed and posed as if they expected to be judged on the grace of an offhand gesture or the curve of a well-plucked brow. A few armored men stood among them, stolid warriors who bore the look of seasoned veterans. Quintus had no love of their breed, but at least they would weigh a man’s worth by the strength of his sword arm and not the cut of his tunic.

With the lift of one finger, Nikodemos silenced the musicians, and all eyes turned from his face to the door.

The escort started forward. Quintus matched his steps to theirs, maintaining a soldier’s bearing. He would show these effete courtiers that a Tiberian faced his fate with impeccable honor and courage. If these were to be his last moments on earth, he would not disgrace himself in the eyes of the empire’s champions.

He stopped of his own accord before the guards could bar his way closer to the throne. He bowed his head the merest fraction, acknowledgment and no more. The courtiers murmured. Danae hid a yawn with slender fingers.

“Quintus Horatius Corvinus,” Nikodemos said, drawling each syllable. A cupbearer obeyed his negligent summons and offered a bejewelled chalice on a chased silver platter. The emperor drank, wiped his fingers on a cloth of white linen and waved the servant aside.

“Son of Arrhidaeos,” Quintus said.

Murmurs grew to soft cries of outrage. Quintus stood unmoved, legs braced apart, hands at his sides. This was not his emperor, nor his lord. He would not call Nikodemos “brother.”

“Son of Arrhidaeos,” Nikodemos repeated. “As you are.” The hall fell silent. The courtiers looked from their emperor to Quintus. An older man, standing near the foot of the dais, muffled a cough behind his hand.

Suddenly Nikodemos laughed. He slapped the fanged lion’s head under his palm, shaking his head.

“It is polite of my Hetairoi to pretend they know nothing,” Nikodemos said, “but I doubt a single one of them is unaware of yesterday’s events. Is that not so, Danae?”

She smiled at him, turning Quintus’s blood hot and cold by turns. “It is, my lord.”

“No one knows quite what to make of it,” the emperor said.

“Do you, Iphikles?”

The old man of the muffled cough bowed and met his master’s eyes. “Such things do not happen without purpose, Lord Emperor,” he said. “But I cannot tell what that purpose may be.”

“A wise answer.” Nikodemos leaned back, stretching his legs. “Who could have predicted the appearance of a royal son believed long dead? Certainly not Baalshillek.”

Courtiers tittered. Quintus noted which men kept straight faces, finding it less than prudent to mock the High Priest even in the emperor’s stronghold.

“My brother,” Nikodemos said. “Such a strange twist the Fates have brought me. And now I must judge what is to be done with him — a boy raised among my enemies. Raised to defy his own father’s empire.”

Quintus felt heat rise under his skin. Nikodemos was baiting him, hoping for some betrayal of untoward emotion. Waiting for a vehement denial…or capitulation.

He would get neither. Quintus held his brother’s gaze and said nothing. “Alexandros,” someone whispered. “Is it truly possible…?”

“Do some of you still doubt?” Nikodemos said in the same tone of lazy amusement. “Uncover your arm, brother. Let my people see how the Stone God left his mark upon you.”

Quintus didn’t move. One of his guards reached for the himation. Quintus raised a clenched right fist, slowly unfolded his fingers and drew the cloth away from his left arm.

Gasps sighed through the room like a rushing wave. Quintus let them look their fill and then readjusted the fabric.

“You see why my father sent young Alexandros away as a babe, to be raised in safety,” Nikodemos said. “Or so he believed.” He nodded to his right. A guard brought another man forward — Philokrates, blinking in the dim light, his hair a wild, white halo about his head. “I owe this reunion to Talos, who served Arrhidaeos so ably.”

Talos, builder of war machines. Quintus hadn’t met his former teacher since he’d learned the ugly fact of Philokrates’s true identity, but he detected no change in the old Hellene. If anything, the inventor seemed more confused and uncertain than Quintus had ever seen him.

“Tell me again, old man,” Nikodemos said. “Is this my brother?”

Philokrates turned his head slowly and gazed at Quintus. His brown eyes held no expression. “It is, my lord.”

“And my father gave him into your care, to instruct while he lived with his adoptive Tiberian family?”

“Yes.”

“You told me of his presence in Karchedon so that he could be of service to me, did you not?”

“Yes, my lord Emperor.”

“And because you hoped to save his life from the High Priest, believing that I would show mercy.”

Philokrates bowed his head. Nikodemos stroked his freshly shaven chin and half smiled at Quintus. “What would you do in my place, brother?” he asked. “If I were the rebel who had killed your men, threatened your chattel, defied your authority — would you show mercy, or risk my continued treason?”

Quintus returned the emperor’s smile. “I would never be in your position.”

“Such humility,” Nikodemos said. “Such foolish courage. But you expect to die, do you not?”

“I expect the same fate as any of my countrymen.”

“You refer, of course, to the rebel Tiberians.” Nikodemos addressed his Hetairoi. “Should we admire his loyalty? Iphikles? Hylas?”

A beautiful young man stepped from the ranks of Hetairoi and flashed kohl-lined eyes at Quintus. “Perhaps he may be given a chance to prove himself, my lord.”

“Indeed. But can the loyalty of such a man be altered?”

“Only if that man is wise enough to recognize his error.”

“That may take some time, Hylas. Would my brother prefer imprisonment or death?”

Quintus opened his mouth to answer, but Hylas spoke over him. “He need not be lonely in his captivity,” he said slyly.

Nikodemos laughed. “Not if you have your will.” He looked sideways at Danae. “Perhaps he prefers other company, my dear.”

“I prefer no company in this hall, Nikodemos,” Quintus said. The emperor sat up and frowned. “I think my noble brother would choose death,” he said. “Do you have a last request of me, Corvinus?”

The Tiberian name was like the whisper of a cold blade against Quintus’s neck. The decision had been made, and there was nothing left to be lost.

“Withdraw from Tiberia,” Quintus said. “Set my people free.”

“I am much too fond of your country for such a sacrifice,” Nikodemos said. “What do you wish for yourself?”

“An honorable death.”

“Honorable. If by that you mean on a sword and not in the Stone God’s fire…” He gestured to one of the officers. The man saluted smartly and bowed to his emperor. His face was seamed with old scars, and he clutched a battered plumed helmet to his cuirass. “I can think of no better man than the commander of my Persian mercenaries to perform such a task. Vanko?”

The soldier moved to stand beside Quintus and drew his curved sword. Quintus looked at Danae without turning his head. Her lips were parted, her eyes glazed with sudden fear. She believed Quintus was about to die.

Quintus had sworn to her that his life wouldn’t end in Karchedon. He’d been so certain. He had achieved nothing…nothing to make this death worthwhile.

“My lord,” Danae said, her voice slightly hoarse. “I beg leave to retire.”

Nikodemos glanced at her in mild surprise. “Squeamish, my lady? You do not wish to witness the punishment of the man who so crudely assaulted your person?”

“Forgive me, my lord, but I do not care for the sight of blood.”

“Gentle Danae.” Nikodemos held out his hand to her. “Would you spare him, then?”

“I would, my lord,” Hylas said boldly. “At least until it’s clear that he is of no use to your majesty.”

“Would you stake your life on his good behavior?”

The slender young man blinked long-lashed doe’s eyes. “My life is my emperor’s, always.”

Nikodemos laughed again. “How can I resist such appeals?”

“Lord Emperor,” one of his officers said, “I advise caution.”

“And cautious I shall be.” He bent his stare on Quintus. “It seems you have allies, Tiberian. And I have more important work at hand. Vanko, your men are quartered in Karchedon.”

“They are, my lord.”

“Select the best to guard my wayward brother. He is to be confined to his chambers. No visitors without my express permission.”

Vanko thumped his cuirass. “As my emperor commands.”

Quintus carefully released his breath. It had all been some courtier’s game to Nikodemos, a test of sorts, and somehow he had passed. Danae had played into the game, and so had the pretty boy Hylas. Now it remained to be seen what Nikodemos expected of him. And how much Quintus was willing to concede to stay alive.

The guards fell in about Quintus. He turned smartly on his heel and preceded his escort back to his quarters. The door was closed and barred. A little while later a maid brought food and wine, which he barely touched. When the angle of light from the small window indicated day’s end, a second visitor tapped on the door.

Quintus recognized the girl who entered, and at once he shot up from his chair and faced the door. Leuke, Danae’s servant, bowed to him and took up a stance of prim watchfulness at one end of the room. Danae followed her. The guards wedged the door half open with the shafts of their spears.

Danae settled in Quintus’s former seat, smoothing her evening robes over her thighs.

“Come here,” she commanded, looking at Quintus down the length of her lovely nose. “I would study the face of the man who dared lay hands on the emperor’s woman.”

She spoke loudly for the benefit of the guards, and Quintus obeyed. He stood close, positioned so that he could be observed by the men beyond the door.

“I regret my discourtesy, my lady,” he said, meeting her gaze.

“No doubt. I confess I was surprised that such a ruffian could be of the royal house. Of course, you were raised by barbarians and know no better. I am inclined, like my emperor, to be merciful.”

“You are gracious, my lady.”

“And you are extremely fortunate.” She glanced at Leuke, and the maid gave an almost imperceptible nod. “If you are very careful,” she said in a low voice, “you may even survive. But you will never touch me again.”

He heard her words and understood their relentless truth, yet his muscles tightened in rebellion. Tiberian discipline kept him in place even as he breathed in the intoxicating perfume of her hair and the arousing scent of her womanhood.

Danae bent in her chair as if to adjust the lacing of her finely-woven sandal. “I have been blessed,” she whispered. “Isis came to me in a dream. She showed me what has become of your friends.”

Quintus leaned closer. “Tell me.”

“They have been given a great task, and the gods will protect them. But they will not return until this task is complete.”

“Where do they go?”

“Into the unknown. That is all I know.” Leuke hissed a warning through her teeth, and Danae nodded in acknowledgment. “I care nothing of what happens to traitors,” she said distinctly, “but you are my emperor’s brother and he will decide your fate.”

She rose, beckoned to Leuke and floated toward the door.

“Do you know the emperor’s game, Danae?” Quintus asked softly.

“He plays no games,” she answered. “He wishes to spare your life. Find reason to let him do so.” She paused, resting her cheek against the door’s polished wood. Her eyes expressed all the things her lips had not, the confusion and fear and conflicting loyalties trapped in her brave and generous heart.

Do not betray him, her eyes said. Live.

Then she walked out the door. The guards closed and barred it. Quintus laid his cheek where Danae’s had been.

“You will never touch me again.”

He slid to the ground and cupped his crippled arm to his chest. In his mind he glimpsed an image of Rhenna and Tahvo and Cian, standing together outside the walls of the city, looking back as if to bid him farewell.

They were free. But they fought for something bigger than mere freedom: the Watcher, the seer and the warrior, bound to each other and to Quintus by some magic as potent as the Stone itself.

I was not meant to go with them. Mine is a different path.

As quickly as the vision came, it was gone. Quintus stood and walked to the high, tiny window overlooking the citadel square. The sun was setting, but summer heat still blistered the pavement. No one who had not seen it would believe that snow had fallen in Karchedon.

No one would believe that a woman could wield a sword like a hero born, that a man could become a beast, or that a Tiberian could be the son of an emperor.

Quintus had begun to believe.

The old man known as Talos came to Baalshillek in all proper humility, head lowered and body hunched. It seemed the inventor was well aware that he had made a deadly enemy in the High Priest, though the two had never met before this day. Because of Talos, Baalshillek’s most valuable prisoner had fallen into the emperor’s hands.

Baalshillek expected no little inconvenience from that fact. As long as Nikodemos believed that Quintus’s power over the red stones outweighed the risk of his rebellious past, the Tiberian remained beyond Baalshillek’s reach.

For the time being.

The Temple Guard left Talos at Baalshillek’s door and withdrew. Baalshillek did not invite the old man to sit. He poured himself a measure of wine—in moderation, of course—and regarded the inventor over the rim of the cup.

“Do you know what you have done?” he asked.

Talos raised his shoulders in a half shrug. “Does the emperor know I am here?”

“I doubt he will object to a friendly visit.” Baalshillek set down his cup. “He may come to doubt the wisdom of listening to your advice.”

The old man peered at Baalshillek from rheumy eyes and looked away. “You would have killed Quintus.”

“Perhaps. Perhaps I would have found a better use for him.”

“Twisting his gifts to suit your purpose?”

“To the service of the Stone God. But your interference has made that prospect more difficult.”

Talos offered no reply. He was either frightened into immobility or a Thespian of considerable talent.

“I could make your life in court extremely unpleasant,” Baalshillek said. “I could turn the emperor against you.”

“He values me. I served his father well—”

“—until you fled and made a bargain for your freedom.”

“To protect Arrhidaeos’s youngest son,” the old man said.

“A son the emperor never bothered to reclaim. One might even say you failed in your bargain, since you allowed young Alexandros to believe himself a Tiberian, traitor to his own father’s blood.”

“An unfortunate turn of events.”

“Most unfortunate—if your pupil chooses to maintain his current loyalties.”

Talos ran his hand over his flyaway hair. “He understands what he faces.”

“That I doubt.” Baalshillek poured himself another digit of wine. “And what of you, Talos? When will you begin building new machines of war for our ambitious princeling?”

If Talos was startled by Baalshillek’s open contempt for the emperor, he didn’t reveal it. “Such machines will benefit you, as well,” the old man said.

“What benefits the empire benefits my god.”

“But the reverse is not always true.”

Baalshillek smiled. “You’re right, old man. That is why you had best consider carefully whom you choose to serve.” He moved to an iron stand that held a wide-mouthed black bowl filled with equally dark liquid. Talos regarded the bowl with wary disgust.

“Do you feel it?” Baalshillek asked, cupping the sides of the bowl. The vessel’s heat passed into his hands, and he hissed between his teeth. “My god’s power is unconstrained by the petty ethics in which you take such pride.” He passed his hands over the surface of the liquid, and it stirred sluggishly.

Talos shuddered. “How many children did you drain of blood to create that monstrosity?”

“How many did you kill with your machines of war?” The mixture in the bowl bubbled and seethed. “You would believe you have changed, old man, since those days of heedless destruction. I know that you had dealings with the rebels who traveled with your former student—the females Tahvo and Rhenna, and the Ailu, Cian. Do you not wonder what has become of them?”

“They are no longer of concern to me.”

“That would be a wise attitude, if true. Let me set your mind at rest.” Baalshillek lowered his face to the bowl and touched his tongue to the liquid. The metallic taste of blood mingled with the unmistakable tincture of the Stone.

The images began to form at once, figures and faces rising to the skin of the fluid, only to drown again. Rhenna of the Free People, tall and lean, with light brown hair, honey-moss eyes and a four-striped scar on her right cheek; Tahvo, shaman of the North, short and compact, with silver hair and blind silver eyes; sleekly-muscled Cian, black-haired and golden-eyed like his lost brother Ailuri; and the rebel known as Nyx, a woman of the South, with skin the color of ebony and eyes like the night.

“They live,” Baalshillek said, letting none of his rage enter his voice. “They escaped the city, and many rebels died to make it so. A few were captured, but they are insignificant.” He dipped his finger into the bowl, then licked it dry. “Your friends, however, must and will be stopped.”

Talos sighed. “I see no mobilization of troops in the city. The emperor seems indifferent to their escape.”

“Because he is wise enough to leave such matters to one who understands them.” Baalshillek caught Talos’s sleeve, forcing him closer to the bowl. “Your friends believe they serve a prophecy that binds them to seek certain great Weapons…a prophecy that foretells the downfall of my god.”

“I know nothing—”

“You know, but it does not matter. Those called the Bearers, the godborn…they have weaknesses to match their supposed powers. And I have sent each of them a gift.” He called up new images, new faces. First Yseul, the female Ailu he had created from the blood and essence of his captive shapeshifters. Then Farkas, formed from Rhenna’s dread of violation and helplessness. And Urho, Tahvo’s twin, dead at his birth but now reborn to haunt her dreams and visions.

“There is no greater weapon than fear,” he said. “My creations were made to serve only one master and achieve only one goal: to stop the so-called Bearers and, if possible, bring the Weapons to me.”

Talos examined the faces, like and yet unlike those of his friends, and shook his head. “You demand much of mere simulacra,” he said. “And perhaps you underestimate simple human courage.”

“You know the worth of your constructions, and I have faith in mine,” Baalshillek said. He cleared the images with a sweep of his hand. “Your companions are beyond your aid, and you will not be permitted to interfere with young Corvinus again.”

Talos stepped away from the stand. “If you are so sure of such things, why did you summon me here?”

“Because you and I are not so different, Talos. They called you ‘the Destroyer’ in the lands your machines ravaged. Yet you saved many lives by ending wars quickly. You made the rebels see the futility of their resistance.”

“Your priests have no need of my devices to achieve the same results.”

A rancid smell rose from the bowl, and Baalshillek summoned an omega priest to dispose of its contents. “You are too modest,” he said when the servant had gone. “You could make yourself very useful to me.”

“You do me far too much honor, lord priest. I fear I must decline the privilege of serving you and your god.”

Baalshillek sat and adjusted his robes around his legs. “You may choose to believe so, for now. But you will keep no secrets from me, old man. All that you have done or been, everything you have ever thought will be as an open scroll to me when my agents have completed their work.”

“I thank you for the warning.” Talos bowed. “If I have your leave to depart—”

“By all means. Return to the court. Draw up your plans and convince Nikodemos that you can put all the world under his heel. I will not tell him that your loyalty is as false as your foolish prophecies.”

“True or false, I am unlikely to see their fulfillment,” Talos said. “You, however, will be alive to witness your god’s downfall.”

Baalshillek touched his stone pendant and pointed at Talos. The old man crumpled, and his face whitened in agony.

“You live on the emperor’s sufferance,” Baalshillek said softly. “How you live is within my hands.”

Talos hobbled to the door and pulled it open with obvious effort. The victory left a foul taste on Baalshillek’s tongue.

No matter. Pain was obviously not sufficient in itself, but the old man had some weakness other than his dubious allegiance to Nikodemos and his fondness for the Stone-killer. Once Baalshillek learned it, no magic would be necessary to convince Talos where his true interests lay. Quintus Horatius Corvinus, so-called Alexandros, would lose his few allies one by one until he was entirely—and fatally—alone.

Chapter Two

Your powers will come.

Rhenna sat on an outcropping of rock on a barren hill, gazing across the valley at the glittering speck that was Karchedon. Early morning sun beat down on her head. No breeze stirred this scorched place where even the city’s fat and glossy livestock did not venture. Yet the fertile croplands nestled between the hills seemed untouched by the scouring storm of dust that had driven the Stone God’s servants back behind their walls.

Rhenna could never again draw breath without being aware of the life in the air all around her … the pneumata and the lesser devas of sky and wind who had come at her desperate call. She had no idea how she had done it or if she could repeat the magic. But it had saved them, and she was changed.

Cian tended Tahvo in a sheltered hollow. The little healer was recovering from the effects of sharing her body with a host of divinities, and would soon be up on her own two feet. The windstorm had won the fugitives time and a goodly distance from Karchedon, but Rhenna didn’t believe for a moment that the priests would abandon their hunt.

“We should move on,” Nyx said.

Rhenna looked up at the dark-skinned southern woman through narrowed eyes. “When was it decided that you should come with us?”

Nyx leaned on her spear and considered her answer. She had deliberately torn the hem of her chiton so that it ended at midthigh, leaving her legs free to move unhindered. Rhenna had tucked her long tunic high under her belt, but she looked forward to exchanging the flimsy garment for a sturdy shirt and trousers. And then there was the matter of a good pair of boots, weapons, and horses for all of them. How she missed reliable Chaimon and Dory….

“You need a guide,” Nyx said, interrupting her thoughts. “My home is south of these lands, and I have traveled this country before.”

This country. Nyx didn’t refer to the hinterlands of Karchedon, leagues of rugged hills and pastures and intermittent streams to the south and west where the Stone God and the empire held sway, and where the risk of capture remained very real. Something even worse than imperial soldiers lay between the seekers and the magical object they sought–-an ocean of rock and sand, roasting under a merciless sun by day and bitter cold by night.

“You have crossed the Great Desert?” Rhenna asked.

“Yes. It is a wasteland few can survive in ignorance.”

“Yet you did not make the journey alone.” Cian joined them, brushing at the dust that clung to his sweat-streaked arms and chest. He had fought in Karchedon as a panther and run naked from the city; the windstorm had bought him time to twist a scrap of cloth around his hips. He was lean and lithe and beautiful, bronzed rather than burned by the sun, an ideal representation of all that was fine in a male physique.

Rhenna had held that body in her arms, felt it move with her own in the most ancient and carnal of dances. She tried not to stare, and to remember what she had vowed to herself when she had agreed to this mad venture. She could not be both lover and leader. She must be–

“I had aid,” Nyx said, oblivious to Rhenna’s turmoil. “There are tribes that live in the desert, and I know where they are wont to dwell.”

“But they are not your tribe,” Rhenna said. “Are your people allied to theirs?”

“Only in our hatred of evil.”

And there was but one true evil that could unite disparate peoples who might otherwise scrap and snarl and fight over booty and borders, just as that evil had unified rebels from a dozen conquered territories.

“Did Geleon command you to help us?”

“I do not even know if Geleon survived the battle. He was my chief in Karchedon, not here.” Nyx frowned. “You are of a most suspicious mind, warrior–-”

“As suspicious as you were when Quintus asked for the rebels’ help in Karchedon.”

“Quintus proved his worth, as you have. I do this of my own will, and because I believe in the prophecies … as did the others who died for the sake of the Bearers.”

Rhenna rubbed her sunburned arms. “Many were willing to give their lives based on the words of one woman–-”

“Your friend, who spoke with the voice of the gods.”

“—and because of these scribblings, which are much talked about but never seen.”

“Philokrates believed in them,” Cian said.

Rhenna snorted. “Philokrates lied about his past with the empire. How can we be sure of anything he told us?”

“The prophecies are real,” Nyx said. “I knew of them long before I came to Karchedon.”

“How?”

Nyx’s expression flattened. “I do not know how Talos obtained his information, but the Stone priests are not the original owners of the sacred texts. They merely stole, or copied. Others outside Karchedon have knowledge of the prophecies, and they will be our allies.”

“Your people,” Cian said. At Nyx’s nod, he added, “then your country hasn’t yet been taken by the empire.”

“No.” Nyx stretched the hamstrings of her long runner’s legs. “The desert lies between Karchedon and my mother’s homeland. Even the Stone God’s minions are not yet prepared to conquer so great a barrier.”

“Then what brought you to the city at such great risk?” Rhenna asked. “Did the prophecies send you, or do you have visions, like Tahvo?”

“I need no visions to see the truth. No one on this earth can escape the Stone God forever.”

They looked as one toward Karchedon. Cian cleared his throat.

“What did you mean when you said I was to carry the Hammer?” he asked.

Rhenna started. She had heard nothing of this, but there had been little time for conversation since the escape. “You have information about the Weapons?” she asked Nyx.

“They are clearly mentioned in the prophecies.”

“Do you know where this Hammer lies?”

Nyx hesitated. “It is somewhere in the south, as Cian guessed. Beyond that I do not know, but there are those in my village, and among the folk of the deep forest, who may help us discover its location–-now that its true Bearer has been found.”

“These prophecies also mention Cian’s name?”

Nyx cut the air with her hand. “Any woman with half an eye could see that he is the one.”

“Indeed?” Rhenna arched a brow. “One would think you have a personal claim on our Cian. Why is that, woman of the south?”

“I believe in him. He is Ailu. He has power over the Earth, and the Hammer is of the Earth. He–-” She broke off, clearly annoyed. “You have known the Watcher far longer than I. Why do you doubt him? Or can it be that you doubt your place at his side?”

Perhaps we should let Cian choose between us, Rhenna thought, scalded with anger. But she recognized the emotion for what it was and clamped the reply between her teeth. Jealousy had no place among the Free People, or in her own heart.

“‘The Warrior, the Watcher, and the Seer,’” she quoted, remembering Tahvo’s words in the rebel safehouse. “Yes, I doubt. But it seems we’re meant to travel together, Cian and Tahvo and I.”

“Earth, Air, and Water,” Nyx said. She rooted the butt of her spear into the gritty soil, chanting in her own language. Tiny buds burst from the polished wood and flared into whorls of green leaves. Living tendrils snaked up and down the length of the spear.

“I am also of the Earth,” Nyx said. “The Watcher is more powerful, but I, too, have my gifts. You may find them useful.”

Rhenna concealed her astonishment and met Nyx’s eyes over the waving leaves. “I put more faith in the other end of your spear, if you’re prepared to fight.”

“She risked her life for us.” Cian said with unaccustomed brusqueness. “I trust you both. Now you’ll have to trust each other.” He pointed his chin toward the arid scrublands to the south, where only a few miserable goats could hope to find sustenance. “You can find these desert tribes, Nyx?”

“I can.”

“And they will be willing to help us?”

“We must be cautious, of course. We will be entering a land where they have fought for survival for thousands of years, but they know the Stone God threatens their very existence.”

“And once we’re beyond the desert?” Rhenna asked.

“Forests,” Tahvo said. She crept up the low hill, feeling her way with outstretched hands. The unbroken silver of that blind gaze was still a shock to Rhenna, filling her with dreadful rage and bitterness. It wasn’t fair that Tahvo should pay such a heavy price for her gifts, and continue to pay as a tool for devas and prophecies.

“I see it in my mind,” Tahvo said, smiling sadly at Rhenna as if she had heard her thoughts. “A vast sweep of trees like the pelt of a great green beast. Not like the North.”

“Nor like the woodlands in the hills west of Karchedon,” Nyx agreed. “You will see many changes between here and my mother’s country.”

“Will there be villages where we can purchase clothing and supplies?” Rhenna asked.

“There is one we may reach by nightfall if there are no further delays.” Nyx inclined her head to Cian. “We should continue on our journey before the soldiers find our trail. If you are ready, Watcher …”

Cian looked to Rhenna, waiting for her signal. A small concession, but it warmed her heart. Dangerously so.

I am leader, she thought. Rhenna-of-the-Scar is no more.

She hitched up her small pack and started down the hill. Nyx caught up and passed her, using her spear as a staff. Cian followed with Tahvo.

They made reasonably good time on foot, using their limited supply of water sparingly. Nyx’s pace never flagged. Tahvo asked Cian’s help when she needed assistance over the roughest places, but the healer fared remarkably well with touch, hearing and smell in addition to the mystical shaman’s senses she possessed.

The land gradually gave up its scant moisture, growing more rocky and bare with every passing league. Dry stream beds carved deep gorges out of overgrazed pasture, stripped of grass and all but the hardiest shrubs. An occasional goat paused in its browsing to stare at the interlopers, and jackals poked their heads from behind jutting rocks, laughing at human foolishness. The air grew so stifling that Nyx called a halt in the shadow of a cliff until the noonday heat had passed.

“The village I spoke of is not far ahead,” she said. “The people who reside there are kin to the wandering desert tribes. They will have horses, which can carry us to Imaziren territory.”

“Imaziren,” Cian echoed, helping Tahvo drink from her waterskin. “This is a name I have heard before.”

“Philokrates called my people ‘Amazons,’” Rhenna said. “A strange similarity.”

“Imaziren is the word for more than one tribesman,” Nyx said. “The singular is Amazi.” She glanced at Rhenna. “Among the desert tribes, women fight at the sides of their men. Your women fight alone, do they not?”

“My people have no kin outside the Shield’s Shadow, except male offspring who return to their fathers among the steppes tribes,” Rhenna said.

“Even your legends don’t tell where Asteria was born,” Cian said.

Asteria, First Mother, founder of the Free People. It was true that not even the Earthspeakers, Healers or Seekers of Rhenna’s race could be sure of Asteria’s origins.

“It doesn’t matter,” she said, watching waves of hot air rise from the baked earth beyond the border of the cliff’s shadow. “As long as these Imaziren help us.”

After the four of them had rested and the sun had begun its downward journey to the West, Nyx led them out again. At sunset they reached the borders of a small, mud-brick village beside a small patch of green Nyx called an amda. Tall, branchless trees with broad, fringed leaves at their tops shaded the houses and the livestock grazing in a surprisingly verdant pasture.

Nyx, who spoke a little of the local dialect, took the coin the Karchedonian rebels had provided and ventured into the town alone. The people Rhenna glimpsed were brown from the sun, men and women both, but their hair and eyes ran from dark to fair, and they wore light garments befitting the hot weather. They came out of their plain, pale houses to talk and sip beverages from clay cups as the cool of evening brought relief from the day’s fierce temperatures.

Rhenna spent most of the next two hours pacing and debating how soon she should go after Nyx. Cian watched her without comment, his chin resting on his knees.

“They are here,” Tahvo said.

Rhenna spun to face the healer. “Who?”

“The spirits. It is difficult to sense them in this land. The water runs deep under the ground, and many of those who once inhabited even the dry places have fled.”

“From the Stone God, as they did in the North,” Rhenna said.

She nodded. “But water rises to the surface in this place, and the spirits linger. Nyx said that the desert tribes rely on the green islands. Perhaps I will be able to talk with the spirits once we are in the sea of sand.”

“If Nyx keeps her promises, you won’t have to burden yourself. You’ve had enough dealings with devas to last you half a lifetime.”

“But it is not over,” Tahvo whispered. “It is only beginning. For all of us.”

Rhenna shuddered. “You’re still mortal, Tahvo. Remember that, when the devas are so anxious to use you.”

But we’re all being used, Rhenna thought. Even the devas.

Cian sat up, nostrils flaring. “Nyx returns. With horses. And food.”

Rhenna hardly thought of nourishment when she caught the unmistakable smell of horseflesh. Nyx led a string of four mounts, one hardly larger than a pony, the others smaller than the steppes breed and far from beautiful, but sturdy enough in appearance.

“It took nearly all our coin to buy them,” Nyx said, offering the lead of a bay gelding to Rhenna. “They’re desert-bred, able to travel on less water than most.”

Rhenna examined the gelding’s legs and patted his shoulder as the animal snuffled her dusty hair. “They’ll do,” she said. She assessed the other horses and chose the tallest gray gelding for Cian, while Nyx took the chestnut mare. The pony might have been made for Tahvo’s short stature and uncertain horsemanship. The tack was not of the best, worn and rubbed thin, but it would serve.

Nyx laid out her other purchases, including larger waterskins for the horses to carry and a change of clothing for each of the riders. There were shirts, trousers and headcloths for Rhenna, Tahvo and Cian, dyed the same ocher hue as the landscape. Nyx had chosen a tunic that left her legs bare. She had bought low leather boots for herself and taller ones for the Northerners. Tahvo’s were decidedly too large.

The meal consisted of flat bread, a thick stew of beans, vegetables and mutton, and a brown drink Rhenna guessed was beer. When the last of the perishable food had been devoured and the rest packed away, Nyx passed out rough woolen blankets and the group made a fireless camp beneath the scraggly branches of a scrub tree. With the horses bunched nearby, Rhenna could almost imagine she was home in the Shield’s Shadow with the herd, back in the days before the devas had spoken to her in voices of wind and blood.

A breeze puffed against her cheek, and she swatted it away. Cian stirred and rolled over to face her, eyes half-lidded and glinting by moonlight. Tahvo snored under her blanket, and Nyx stood watch near the horses, her lean body erect in a warrior’s stance.

“You can’t sleep?” Cian asked.

Save for brief conversations, the two of them had barely spoken since formulating the plan to leave Karchedon. So many deaths, so many sacrifices stood between that day and this. So many vows that Rhenna wasn’t sure she could keep.

“I could ask the same of you,” Rhenna retorted. He was almost within reach. If she stretched her arm and fingers…

Cian shivered. “They must be pursuing us,” he said.

“Do you know this, or only fear it?”

“I’m always afraid.” He raised himself up on his elbow. “I’m afraid for Tahvo, that she’ll be driven mad by the powers that consume her. I fear for Nyx and her disillusionment when she sees how unworthy I am of her expectations. And I fear for you.” He spread his right hand on the ground between them, the hand that lacked its smallest finger. “Rhenna—”

She willed him not to speak of things that could only create more discomfort for them both. But his eloquent golden eyes said all the words his tongue did not, bringing a slow, heavy throbbing to the core of her body.

“Would you change what happened?” Cian asked.

He had no need to explain himself further. She remembered a garden lush with flowers and trees, untouched by the impossible snow that fell throughout Karchedon. Lying with a man she had wanted without daring to admit it, giving and taking in equal measure. Knowing there could never be a moment’s peace or certainty between them.

“I would not change it,” she said. “But that was a place out of time, Cian. We can’t go back.”

He closed his eyes. “If your people could remain free of the Stone God, would you return to them?”

She rolled over, turning her back. “We wouldn’t remain free. And the Ailuri are gone. The Free People can never be the same again.”

His fingers stroked over her shoulder, so lightly that she felt their heat more than their touch. “None of us can. But we must stay true to what we are, Rhenna. To each other.”

Mother-of-All. She tugged the blanket up to her neck. “I swore I wouldn’t leave you while our quest continues.”

He retreated, and for an instant she thought he had left the camp. She strained her ears for the sound of his breathing.

“I promise the same,” he said at last. “I won’t leave you, Rhenna, until the Stone God has fallen.”

And after? If there was any future to be had, it was far beyond Rhenna’s ability to imagine. Survival was by no means assured, not for any of them. The devas knew she would willingly give her life for Cian or Tahvo.

“Go to sleep, Cian,” she said wearily. “Surely Tahvo will sense if we’re in immediate danger.”

But Cian didn’t answer. He had gone, perhaps to prowl the night in a panther’s skin black as the night sky. Rhenna looked for Tahvo’s sleeping form, got up and spread her blanket closer to the healer. She laid her sword within easy reach of her hand.

Tahvo muttered something in a language Rhenna didn’t understand. “Heru-sa-Aset,” she whispered. She smiled tenderly and began to sing an unmistakable lullaby.

“She speaks of the gods,” Nyx said. She crouched beside Rhenna, lean hands dangling between her knees. “Heru. Horus, the Hellenes call him, child of Aset and Asar, Isis and Osiris.”

Rhenna sat up, tossing the blanket aside. “I’ve never pretended to know much of devas. Are these important?”

“They are revered in Khemet, and by some in lands beyond.” She peered at Tahvo. “That one knows much she cannot yet say.”

“She knows more than any of us can understand.”

“Then perhaps she would tell you what I am about to say, though you will not wish to hear it.”

Rhenna’s heart began to thump in her chest. “And just what is that?”

“You care greatly for the Watcher, do you not?”

“Of course I care for him.” Rhenna got to her feet. “We’ve been companions for many months. We’ve saved each other’s lives. I care for Tahvo—”

Nyx shook her head. “Do not pretend to misunderstand me, warrior. I may not be well acquainted with your past or your customs, but I recognize the gaze of lovers when I see it.”

Rhenna flushed. “Perhaps your sight is not as keen as you believe.”

“Then you deny that such a relationship exists?”

Relationship. Rhenna hated the sound of Cian’s name on Nyx’s lips, but this was a subject she had no wish to discuss with a virtual stranger. “What may exist between Cian and me is our business,” she said sharply.

“But it is not.” Nyx stood, her dark eyes clouding with anger. “It is the business of the world, of all who fight the Stone God. You have no comprehension of what lies ahead. Through Tahvo, the gods revealed only the smallest part of the battle to come. They revealed that you are one of the godborn Bearers. And Cian is to carry the Hammer.”

“You already made that clear enough,” Rhenna said. “If you think I’ll stand in his way…”

“Perhaps not deliberately. But the Watcher will have no time for ties such as those he believes bind you to him. He must be free.”

“He is free.” Rhenna turned away, fighting to still her trembling. “The Ailuri and the Free People have been allies for all our known histories. I would protect Cian even if I had met him yesterday, just as any of my Sisters would defend any of his kind. But I am a warrior, not one of the Chosen.”

“The Chosen,” Nyx repeated softly. “Chosen by the Watchers?”

“Chosen by our Earthspeakers to mate with the Ailuri.” Rhenna’s voice cracked, and she swallowed to bring it back under control. “I owe you no explanations, Nyx of the Unknown Lands, yet I will tell you this. Cian’s choices are his own, but he is not all-powerful. I would have come even if Tahvo’s spirits had declared me one of the deva-cursed godborn, because he is alone and needs guarding as much from himself as from those who would destroy him.”

“And you trust no one else to watch the Watcher.”

“I trust very little.”

“And yourself? Do you trust yourself, Rhenna of the Free People, who has mated with one who should have been forbidden to you?”

Rhenna reached for the knife at her waist but diverted the motion, clenching her fist on empty air. “You assume a great deal, Nyx,” she said. “You think me weak, like women of the Hellenes. Do not make that mistake.”

“Then you will give him up for the sake of our quest?”

Rhenna laughed. “Give him up? Is he a dog to wear a collar? Do I hold his leash?”

“It is not enough to deny your feelings. You must be prepared to push him away if he comes too near. If you refuse, you may bring about his death and the downfall of everything we hold dear.” She kicked a pebble with the toe of her boot. “One distraction, one misstep could prevent him from doing what he must to win and hold the Hammer. You could be that distraction, Rhenna.”

“Your opinion of Cian is as low as it is of me.”

“You are wrong. I have great respect for you, as a warrior and as one of the Bearers. I believe in the Watcher with all my heart. But what men and women call love can be a terrible force. It has no place among the godborn. Cian’s attention must be focused on victory. When your time comes to claim your Weapon, you, too, will be alone.”

Alone. As if she hadn’t been alone all her life. As if that one time with Cian hadn’t been born as much of accident as intention.

No accident. The devas themselves arranged it. We were meant to be together….

“No,” Rhenna said. “I will not be this ‘distraction’ you fear. Cian and I are not lovers. But I won’t abandon him.”

“That is not required.” Nyx’s shoulders sagged as if she had unexpectedly emerged alive from the heat of battle. “He will need your protection, and one day you will stand together as Bearers. But only as Bearers.”

“I thank you for making my position so clear.” Rhenna backed away before she could consider striking at this woman with her overweening arrogance. She grabbed her sword and climbed to the hill overlooking the village. Gusts of wind blew first from the North and then the South, sighing the warning that had become so familiar.

Danger.

Rhenna laughed.

Chapter Three

“I say we are wasting time,” Farkas said, his lips curling in a sneer. “They can’t be very far ahead now. We should attack while we’re close to the city.”

“When we still know so little about their powers?” Urho said, staring at his fellow male with undisguised contempt. “Can you make a great wind like the warrior female, Skudat? Or are you merely ruled by hatred of the one who helped give you birth?”

Farkas snapped the brittle stick he held between his hands and tossed the two pieces aside. “As you hate the healer? You wouldn’t exist without her. At least I—”

“Be silent,” Yseul hissed. The males looked up at her as if they were surprised she dared speak. Even after days of traveling together, they quarreled among themselves like infants…and infants these creatures were, only weeks old in the ways of the world.

Yseul was wiser. Baalshillek had brought her to life nearly a year ago, when he had taken flesh and blood from captured Ailuri and created a shapeshifter of his own. Female of a race where females were unknown. Driven by hungers she hardly understood, given new form on the day she met and seduced the Ailu named Cian.

Cian, her enemy. She grew hot and wet at the thought of having him at her mercy once more.

She rose from her seat on the rock above the others and stretched, bending and twisting until the stupid males gaped in mute lust. She had not bothered to clothe herself since her last change from panther to woman, but she wasn’t afraid of her companions’ frank desire. She wasn’t for them, and they knew it.

As for the Children of the Stone, the soldier escort Baalshillek had so generously provided for his creations, Yseul doubted they felt real emotion at all. They seemed no more than three dozen armored puppets. Yet among those warriors was at least one who had been sent to spy on her and her fellow simulacra, one who had been given the independence to judge the progress of their mission and report any failure to Baalshillek.

Sharp pain stabbed Yseul’s forehead, and she rubbed at the shard of red stone imbedded in her flesh. Even a mildly treasonous thought was enough to loose the crystal’s punishment.

“Farkas,” Yseul purred. “Urho.” She climbed down from the rock, finding her way easily by moonlight, and stopped before them. “You both know why we were sent to this gods-forsaken land. Our lord Baalshillek has given us but one purpose, and that is to stop the godborn—”

“And take the Weapons,” Farkas interrupted.

“If possible,” Yseul agreed. She stroked the barbarian’s chin with the tip of a long fingernail. “Urho is right. If we attack now, we do so in ignorance. Already Rhenna has proven herself stronger than we anticipated, and her powers may grow. She is to be one of the Bearers.”

“How can any female wield a weapon forged for heroes?” Farkas demanded.

Yseul smiled and ran her tongue along the edges of her sharp teeth. “You tell me how Rhenna’s people continue to hold the Skudat and other tribes at bay, mere women though they are?”

“I remember taking the bitch,” Farkas said, jerking away from Yseul. “She was helpless. I could have killed her any time.”

“You seem to forget, my impetuous friend, that it was not you who enjoyed her scarred body. You are but a shadow of that other Farkas…and he did not kill her.”

“I am Farkas,” he said, beating his chest with his fist. “I am more than he ever was or can be. I hold the power of Air.”

“Prove it.” She folded her arms beneath her full breasts, lifting them high. “Show me your skill, Skudat prince.”

He licked his lips as if he dreamed of suckling on her like the babe he was. “I have many skills, woman.”

“Then make a windstorm, like the female you conquered.”

Farkas snarled defiance and lifted his hands. His dark eyes squeezed shut. Drops of sweat stood out on his forehead. A fitful gust of air played around his feet and scattered dust over his boots.

Yseul laughed. Urho snickered. Farkas swung toward the shaman’s double, but Yseul stepped between them.

“You are not ready,” she said to Farkas. “And you, Urho…if you had been born to a human woman, you would have had Tahvo’s abilities. That birthright was denied you, but our master has given you power over the element of Water. How well can you use it?”

Urho scowled, his pale eyes reflecting light like twin silver pools. “I will learn.”

“And learning takes time.” She ran her hands over her flat belly and flung back her head. “Time we have, my fellow travelers. Our enemies have far to go. There will be many chances to hurt them and to make them realize the futility of their hopes.”

“You speak like a feeble enaree, woman,” Farkas said. “What will you do when it’s time to fight?”

She changed instantly, confronting him with a panther’s bared fangs and lashing tail. He flinched, in spite of all his bravado. She could kill him…and earn Baalshillek’s undying wrath. Proving her superiority would be far more satisfying, if she were patient. Patient as a cat waiting for a small rodent to emerge from its hole.

With a single thought, she was human again. “I have a power neither of you possesses,” she said, almost sweetly. “And I am Ailu. The Earth is mine as much as it is Cian’s.” She crouched and passed her hand over the dry dirt. A small crack opened at Farkas’s feet. He cursed and jumped back.

“Until one of you has a plan worth following, I will lead this party,” she said. “I suggest you practice to refine the skills your creator gave you. I would not like to see him disappointed.”

Farkas spun on his bootheel and strode away, shoving the Stone’s Children right and left out of his path. They closed ranks immediately and looked to Yseul for orders.

Which of you is Baalshillek’s spy? she asked them silently, ignoring the pain in her head. I will find you. I must.

“At dawn we continue our pursuit,” she said, addressing the commander of the phalanx. “You will send scouts ahead to question any villagers in the vicinity…discreetly. We want no dead in our wake. Not yet.”

The commander—nameless, just as he was faceless behind his slitted helmet—saluted. His men dispersed to their beds on the hard ground, long spears hugged to their bodies like lovers.

“You have won…this time,” Urho said. “Farkas will not be content to follow a female forever.”

“Farkas is a fool, and he had better gain wisdom quickly. There can be no failure if we wish to continue our existence.”

Urho eyed the Children. “They have been sent to watch, as well as serve us.”

Indeed. But perhaps a time will come when we no longer…require their services.

She noted Urho’s narrowed glance and smiled. “Do you also have ambition to lead, Urho?”

“Unlike Farkas, I do not hate all females,” he said. “But beware, Yseul. If you fail in your vigilance, it will be observed.”

“I take your warning,” she said. “We must be allies, but we are not burdened by love for one another, as are our enemies. Do you understand love, Urho?” But Baalshillek is. And if he sees us now, it will not be so forever. Eventually we must venture even beyond the limits of the Stone God’s influence.

And when that time comes…

“Do not worry, Urho. You are a most obedient servant. You will receive your reward.”

And so will I. Beware, Cian of the Ailuri. So will I.

Among many of the peoples Cian had known during his youthful wanderings in the North, it would have been unthinkable that two women should lead while the man obediently followed.

Cian did not find it strange. He had been born to a mother of the Free People, those the Hellenes called “Amazons,” and lived beside them in the Shield of the Sky until his sixth year sent him back to his sire’s race. He knew women could fight and ride with the best of men, and he never doubted their courage.

He had seldom been the only male among females. But he had felt alone many times, both more and less than human, and he had known what it was to be helpless. Now, as he and the band of seekers began the trek across the Great Desert, his only use was to trail behind Nyx and Rhenna, caring for Tahvo as best he could.

“I know it is a human weakness.”

Like fear, and greed. But not ambition. Not the desire for the power one had been created to wield. “We are not human, Urho.”

Tahvo herself was no weakling, but her blindness was still new. Her other senses were growing stronger, and Cian taught her how to listen and smell in the way of the Ailuri—how to catch the slightest shift in the wind or detect the faint rattle of a bird in a thorn tree. She could already find water in the least likely of places. Yet it was clear that something troubled her.

“What worries you, Tahvo?” he asked when their little group had left the last of the rocky hills and coastal valleys behind. “Do you sense our enemies?”

She shook her head. “It is the spirits. I had hoped to find them once we were far enough from Karchedon, but…” She paused, as if seeking the right words. “If they still exist, they hide deep under the ground or high in the air, where I cannot reach them.”

That was troubling news indeed. Tahvo was the travelers’ go-between with the devas. Through her, in Karchedon, the devas had explained that the coming war would require all the resources of free men and benevolent gods in every corner of the world. Even the most barren places had their lesser devas…unless they had been destroyed or driven away.

Cian looked out on the flat pan of black rock and sand stretching before them as far as the eye could see. He followed the erratic flight of a small, shiny black beetle as it winged past his horse’s ear. The desert was hardly as lifeless as it seemed. Beyond the realm of plowed fields and livestock, where the gravel plain began, wild creatures filled every available living space, no matter how inhospitable to men. Lizards, scorpions, serpents, dust-colored birds, even the occasional big-eared fox, scuttled between larger rocks in search of shade by day and prey at night.

Nyx took her cue from the beasts. When they reached the open desert, she urged travel during the hours of darkness as long as the moon provided adequate light. She usually called a halt by mid-morning, when a haze of heat softened the harsh horizon with the illusion of moisture, and the travelers sought scraps of shade beneath nearly leafless thorn trees or clusters of boulders. Everyone slept, the horses dozing on their feet. As night approached, Nyx built small fires of whatever material was available and made flat cakes out of a paste of grain and water baked in the embers.

Every day was much the same. That first week, and the second and third and fourth passed with monotonous discomfort. The ground remained featureless save for colored swaths of pebbles and the isolated hillock. Only the light itself changed, brilliant ocher as the sun rose in the East and fading to a white-hot glare at noon. There was no rain, no rivers or streams; sometimes the pattern of rocks revealed where flash floods from some rare and ancient storm had scoured channels out of the desert floor.

Rhenna rationed the water carefully, saving the greater part of it for the game little horses. Nyx led them to wells painstakingly dug into the rocky earth where water rose nearest the surface; she, Cian and Rhenna took turns hauling up leather buckets of gritty liquid to refill skins and quench unrelenting thirst. Tahvo always listened for the spirits who should inhabit the realms of Water but found the wells as deserted as the arid plain.

Nyx watched constantly for signs of the desert tribesmen, but the Imaziren remained elusive. Rhenna grew more grim as the leagues passed.

“The animals can’t abide these conditions much longer,” she told Nyx as the women shared the morning’s meager supply of water. “We’re almost out of grain, and there isn’t enough grazing even beside the wells. Where are these desert folk of yours?”

Nyx gazed toward the Southern horizon. “Have patience,” she said. “They will come.”

“Patience will not carry us when the horses are dead.”

Cian watched the two women in wary silence. Before this journey began, he would have sworn that no woman in the world could be as stubborn as Rhenna of the Free People. But Nyx shared that quality in full measure. In Karchedon she had been one of many rebels, subordinate to the leader Geleon; she’d been a prisoner of the Stone priests and barely escaped with her life. But there was something in her carriage that suggested a very different past. She was as proud as an Ailu in the days before the Children of the Stone came to steal Cian’s people from the Shield, and her courage was admirable.

Admirable. Cian shifted uneasily on his mount’s back and tried to wet his cracked lips. He couldn’t deny that he was drawn to Nyx in a way he couldn’t define. Her powers were of Earth, like his; she was graceful and beautiful. Rhenna had ignored Cian since that night outside the village, and it was Nyx who asked how he fared, who treated him as an honored companion.

Once or twice at the afternoon camp Cian caught Rhenna looking at him by the wan firelight, but she always turned her head before their eyes could meet. He knew that she didn’t dare show any sign of weakness now that she’d placed herself at the head of their expedition. Affection was an encumbrance for a warrior, even one who had given her body and some small piece of her heart to the man who rode beside her.

Cian wouldn’t beg for her attention. He’d lost nearly all right to pride, but that remnant lingered. When Rhenna kicked her mount into a trot and Nyx fell back to join Cian, he had his emotions under control.

“You are well, Watcher?” Nyx asked.

“Well enough. Where is Rhenna going?”

Nyx adjusted the cord that bound her headcloth over her braided hair. “Ahead, to scout. She won’t go far.”

Cian scanned the horizon, where Rhenna’s vanishing shape was a distorted blur in the rising heat. “What does Rhenna hope to find?” he asked.

“I think she has begun to doubt that we will meet the Imaziren,” Nyx said. “Do you share her distrust in me, Watcher?”

Cian sighed. “You’ve told us very little about your part in this journey. Perhaps if you explained, Rhenna would be less suspicious.”

“Of my motives?” Nyx tossed her head. “I intended to do so, but she can make such conversations difficult.”

“She prefers action to discussion,” Cian said wryly.

Nyx curled her fingers about the shaft of her spear, which rested in a makeshift harness of rope tied across her horse’s withers. “Action is not always possible or advisable,” she said. “I would have you understand, even if she does not.”

Cian reined his gelding to a stop. “You had better make clear what you expect of me, Nyx, or I may sadly disappoint you.”

“That is not possible.” Her dark eyes glinted with passion. “You are the one. The one my father sought, the one written of in the prophecies.” She glanced back at Tahvo, who rode her stolid pony with eyes half closed. “I will tell you some of what you wish to know…but I ask you to say nothing of it to the others until I am ready.”

“If it puts them at a disadvantage…”

“It will not.” Nyx shifted her slender weight and urged her horse into motion again, her spine strong and flexible as a willow branch. “I must begin with my father. You see, he was not born in my mother’s land. He came from the East, from a city unknown to all but a privileged few. His people call it New Meroe.”

“I’ve never heard of it.”

“If you had, my father’s people—my people—would be in grave danger.” She met his eyes. “New Meroe is the true home of the prophecies, the ancient writings that predict the rise and fall of the Exalted and the Stone God. It was from there that my father left in search of the Hammer of the Earth, and it was his quest that sent me across the desert to find what he could not.”

Nyx continued her remarkable tale as they rode through the morning, while Cian listened with astonishment and growing apprehension.

“So at last I arrived in Karchedon,” she said, her voice grown hoarse with the story’s telling. “I heard rumors of panther men taken captive by the Stone priests. I joined the rebels in the hope that Geleon would work to free the Watchers, but his people hadn’t the strength for so desperate an act. Then you came.”

“Ignorant of everything but what Philokrates had told us,” Cian said.

“As I was ignorant of your presence when Quintus and Talos asked for our help. But after Danae set me free and I met you, I knew you were the one.”

“How? Other Ailuri escaped from Baalshillek—”

“They were not chosen.”

“I would rather have died with them.”

“No.” She jerked on the reins, and her horse tossed up its head. “Do you think that Rhenna and Tahvo would long have survived your fall?”

“I didn’t save them. I didn’t save anyone. Many lost their lives because of me—”

“What you will save is a thousand times more important than any one life.”

Cian laughed. “The world?”

For a long time Nyx didn’t answer. “Not only the world’s body, but its soul.”

Cian had learned from experience that there was no arguing with the faithful. “What of the Weapons? We were told that each of them is guarded by an Exalted who escaped the Stone prison. Do your prophecies say which deva took the Hammer?”

“They tell that the god of chaos, Sutekh, created the Hammer to fight the Exalted, but they do not reveal who stole it.”

“And the other three Weapons?”

She bit her lip. “My father was able to share with me only what he knew. The priests of New Meroe understand far more than a simple warrior. When we take the Hammer—when you take it—we must continue on to the holy city.”

Cian heard the conviction in her words and wondered what Rhenna would make of them. She would certainly object to Nyx deciding the seekers’ destination, but she knew they had all too little information to go on. If New Meroe held the key…

“Was it your father or your mother who gave you your gift with growing things?” he asked.

“My mother. Clan Amòtékùn is blessed with such abilities, passed from mother to daughter.” She hesitated. “What became of the females of your people, Cian?”

The question startled him. “We have no females,” he said slowly. Liar. There is one…unnatural, forbidden….

He shook himself. “We…take mates from among the Free People, whose country borders our mountains. Male children of such matings return…returned to us in their sixth year.”

“No female has ever been born with the shapeshifting gift?”

“None. Female children of Ailuri sires usually became leaders among the Free People, but they did not change their shape. Why do you ask?”

“Did you not find it lonely without mates of your own kind?”

Cian looked away. “Our elders said we were meant to be alone, close to the devas and apart from man. We had no need of such companionship.”

“Yet you left your people.”

“I was not content with the life to which I was born, so I left the mountains. When I finally returned my people had all been taken.”

“And you blame yourself. This is an indulgence you cannot afford, Watcher.”

He almost smiled, thinking again how much she sounded like Rhenna in one of her more reproachful moods. “I doubt there will be many indulgences for any of us,” he said.

“Sacrifice is necessary if great deeds are to be achieved.”

“What else do you demand of me besides saving the world?”

She looked into his eyes. “Your courage and strength, when the time comes to leave behind all that you love.”

He knew what she meant, and the beast within him howled in protest. The blood raced hot in his veins. His mount plunged, feeling the wildness simmering under his skin.

Nyx reached across the space between them and took his hand. “I have faith in you, Cian of the Watchers. You will defeat the god of evil and take your rightful place.”

“Where? On a temple pedestal, with priests of his own to worship him?”

Rhenna’s voice was tight with feigned amusement, and her eyes were slits in a dust-coated face. She drew her horse alongside Cian’s and pushed straggling hair from her forehead. “It seems I’ve missed a fascinating discussion,” she said. “Perhaps you can share it with me.”

“I doubt you’d find it of interest, warrior,” Nyx said. She and Rhenna glared at each other. A sharp burst of wind blew up from beneath the horses’ feet, carrying grit into Cian’s eyes.

“The wind is rising,” Tahvo said, trotting up to join them. “We must find shelter.”

Cian sneezed. The air was already laced with tiny particles of dust and sand, blotting out the horizon and turning the very ground into a whirlpool of earth and pebbles.

“This should not be,” Nyx said. “It is the wrong season for windstorms, or I would have been prepared—”

“Prepared or not, it comes,” Rhenna said. “Where do we ride, Nyx?”

The Southern woman sat still on her trembling mare. “Cover your faces and follow me.”

She turned her mount into the wind. It seemed insanity, and as the gusts grew more violent the sting of spinning gravel became lashing whips, tearing at skin and cloth with equal viciousness. The air was too thick to breathe. Cian lost sight of both Nyx and Rhenna. Guiding his horse with his knees, he reached for Tahvo’s reins and tugged her pony as close as he dared.

Soon every step was a struggle for the terrified, half-blinded horses. The exposed portion of Cian’s face was a mass of tiny welts and abrasions. Blood trickled into his eyes. If shelter lay ahead, he couldn’t sense it. He and Tahvo might have been alone in a world of unbeing.

“It is Rhenna!” Tahvo shouted, muffled by the cloth wrapped over her mouth. “This wind is of her summoning.”

“I can’t see her,” Cian replied. “I can barely smell her. Can she control it?”

“Only if recognizes her own magic. She must understand….”

But Rhenna obviously didn’t understand. If she’d created this storm as Tahvo claimed, it had come not from her will but from her anger. And if she didn’t find a way to bring it under control, she would surely kill them all.