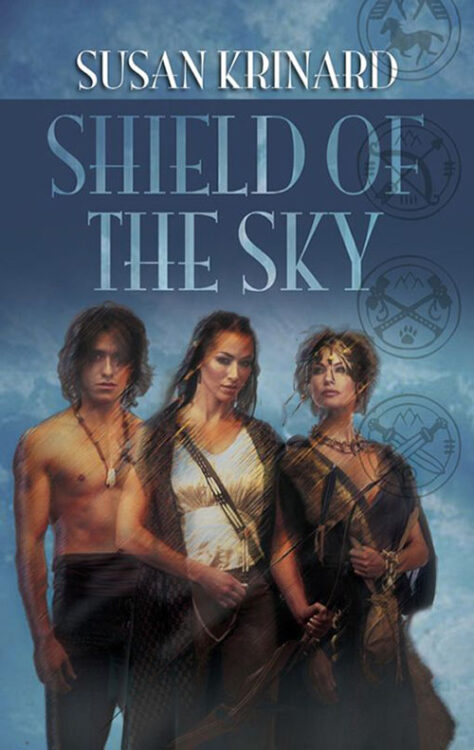

The Stone God Duology, Book 1

Shield of the Sky

Ever since witnessing a sacred ritual, Rhenna of the Free People has been isolated. Not outcast, yet not part of her tribe, she walks alone, guarding the land’s borders. And growing more troubled by the changes in the wind. Anger and war are rising. The mountain-dwelling shapeshifters—partners to the Free People—are disappearing, and word has come of an evil new god: The Stone God, whose followers are known by the red stones they hold and the chaos that accompanies them.

So when Rhenna hears that a shapeshifter has been captured by the Stone God’s servants, she must rescue him. Now Rhenna is embroiled in a dangerous game as the forces of evil and nature fight to control humanity’s future.Together with a growing band—the enigmatic shaman Tahvo, the panther shapechanger Cian and the rebel Quintus of conquered Tiberia—she must travel the world, seeking to prevent its destruction.

Whatever danger lies ahead, the downfall of the Stone God has begun….

Read an Excerpt

Prologue

Forbidden.

It was a word Rhenna had heard seldom in her childhood. Until she was six, she had gazed at the snow-capped peaks of the Shield of the Sky and known the great mountains only as protectors, home of devas, guardians of the lands of the Free People which stood in their shadow.

But when she reached the age of first testing, and the Earthspeakers found that she bore no special gifts to belie her common parentage, she was taken to the foot of the Shield by her mother’s sister and told what she must never do.

“The Shield is forbidden to you,” said the blacksmith, whose arms were broad as oak branches. “Only the Chosen climb the hills, at the appointed time, to meet with the Ailuri.”

Many years passed before Rhenna knew what her aunt had meant by her cautious words, the small warding gestures and averted gaze. Pantaris feared nothing, neither longtooth cats nor brutal steppe storms nor barbarian raiders.

Yet her warning burned deep, scarring with curiosity, and Rhenna could not remember a day when she had not looked up at the Shield and longed to discover its secrets.

Today is the day.

Rhenna shifted in her crouch behind the boundary stone and gazed up the broken slope over which her sister had passed. The world had altered much in fourteen years. Pantaris’s hair had gone gray as the iron in her forge, and Rhenna no longer saw the world with the eyes of green youth. Her arms were strong, her aim true, her skill respected among the Sisterhood. She wore her brown hair in the braids of a woman grown.

Only her desire had not changed. No one would believe that the devas spoke to her—yes, even to a mere warrior; that they came as breaths of air or gentle breezes or howling winds, wordless and strange. Always they bade her look to the mountains.

Now Rhenna, daughter of Klyemne, Sister of the Axe, gazed upon the path of the Chosen and knew she would risk everything to see that which was forbidden.

She glanced behind her, past the carved axe-handle that stood over her shoulder. The others had all gone: the sisters and aunts and mothers weeping at the honor bestowed upon their kin; the Earthspeakers who presided over the ceremony of leave-taking; the warriors standing guard as they had always done, silent and stolid.

Not one of them had seen Rhenna linger. If they had, they would not guess her purpose. It was unthinkable. Inconceivable.

Forbidden.

She lightly touched each of her weapons, whispering a prayer for luck, and removed them one by one. First was the great double-bladed axe, which she laid on the bear pelt she had spread beside the stone. Her gorytos, the side quiver with its precious burden of bow and short arrows, joined the axe. Then came the belt knife, longtooth-hilted, and both of her boot daggers.

Last of all she removed her cap. She folded the leather neatly atop the pelt and unbraided her hair, letting it fall loose about her shoulders.

Kneeling beside the pelt, Rhenna chanted the song of preparation for battle. She touched her forehead to the boundary stone and begged its favor, spread her fingers against the soil and did the same. She opened her heart for all the devas to see.

Then she rose to her feet and trod the winding path among the oaks, ascending as a hundred Chosen had done before her. Soon she was in the pines, and still the way led up and up. If she looked back, she would see the steppe spread out below like a map painted on rough skin.

She did not look back. The single path began to separate, sending faint strands hither and yon like an unravelling skein of wool. She knelt and studied each branching and followed that which bore her sister’s bootprint.

Soon.

The air of summer was warm even here, where deva winds caressed the hillsides. Red deer grazed in lush meadows, unafraid of ordinary predators.

Rhenna stopped to swallow the sudden thickness of fear. She loosened her jacket to let the breeze flow freely under her shirt to dry the sweat on her skin. If the devas were against her, surely they would have made themselves known by now.

Once more she climbed. The path did not branch again. After half a league she found a pile of abandoned clothing, discarded with no semblance of order. Rhenna almost smiled. So like Keleneo, who had been Chosen for the Seekers because she could never keep her thoughts on the work at hand….

A strange scent came to Rhenna, and she lifted her head. The small hairs rose at the back of her neck. She walked more slowly, listening. Great boulders rose like sentinels. She sucked in a breath and rounded a giant, pitted rock burnished silver by the elements.

There, in the shadow of a twisted pine, lay a wedding bower. Keleneo stood beside it, repairing a hole in the curved, willow-bough wall with deft fingers. Wind blew her transparent shift against her body, picking out the tight buds of her nipples and the long lines of waist and thigh. She didn’t so much as shiver. The devas would not allow her to suffer. She was Chosen.

Rhenna closed her eyes and imagined herself in Keleneo’s place. She would not wait so calmly. She would stand facing the peaks, watching, alert for the first rustle of leaves or padded footfall. Her pulse would race like a yearling colt. She would imagine him coming to her from the heights, imagine what it must be like to couple with the descendent of a god….

No sound, no scent tore Rhenna from her dreams. All her senses shouted as if she had walked through fire and jumped into an icy torrent.

The Ailu flowed down the hillside like an obsidian river, seemingly boneless, his black coat agleam in the waning sunlight. Huge, disk-shaped paws wove noiselessly among the rocks. His golden gaze struck sparks from the earth.

Mother-of-All, he was magnificent. No whispered tale could do him justice. And Rhenna knew true fear, that she should look upon this magnificence without paying a terrible price.

Keleneo was not afraid. She moved gracefully away from the bower and waited for her lover, arms raised in a gesture of welcome. The Ailu covered the remaining distance almost daintily, as if he might send her tumbling with one misstep.

He touched the point of his black nose to Keleneo’s outstretched fingertips. She fell to her knees among the flowers she had gathered, dipping her forehead to the ground at the Ailu’s feet.

That was when the miracle happened. Rhenna blinked, and in the space of a moment the Ailu was beast no longer. He stood before his bride a naked man, rampant with desire, fully as magnificent as the great cat he had been. Black hair spread across his shoulders and spilled nearly to his waist. His face was beautiful. He laid his broad hand on Keleneo’s head.

Keleneo didn’t speak. She pressed one hand to her breast and then brushed the Ailu’s erection with a feather-light caress. He flung back his head and shuddered.

Rhenna’s throat ached with unshed tears. You were not Chosen, the Sisters exclaimed. Shame, cried the Earthspeaker, pounding her oaken staff into the ground. But there were other voices like wind in Rhenna’s ears, and they told a different tale.

Here you belong, they said. Here ...

Something moved at the corner of Rhenna’s vision. She spun, hand reaching for the knife she no longer bore. Startled eyes met hers—yellow eyes in a brown, masculine face much too old for one of the village children.

Not a child, but a boy on the very edge of manhood. He was naked, shivering, his thin body strung with muscle that could not keep pace with his bones. He tossed black hair out of his face and grimaced in alarm.

An Ailu boy. The thought had scarce taken shape in Rhenna’s mind when she heard the roar behind her and followed the boy’s terrified gaze.

Keleneo shrank into the shadow of the hut, hands pressed flat over her mouth. Her Ailu mate screamed in rage. He changed from man to beast in a heartbeat and crouched to spring.

Rhenna flattened herself to the boulder and swung back to the boy. She never knew what she might have demanded of him, for he was already gone.

She clenched her fists and stepped out to meet her fate. Blood drummed behind her ears. The devas led me here. They will protect me.

Black flashed across Rhenna’s vision. No deva appeared to intercede. Her belly tightened in anticipation of the killing blow.

“No!”

Keleneo’s voice, riven with horror. The blow never came.

Rhenna opened her eyes. The Ailu crouched an arm’s length away, tail lashing, fur stiff along his spine. His teeth gleamed in jaws that could crush a woman’s skull in a single snap.

Death Rhenna could have accepted. But his glorious, golden eyes conveyed punishment beyond bearing … all the scorn, the utter contempt of the Elder-Council judging the blasphemer.

Forbidden.

Rhenna didn’t even have time to flinch when the Ailu reared up upon his hind legs and lunged, striking at her head. Searing pain came many long counts after the blow, as if the claws had torn the skin of some other face.

Someone wept. The Ailu spun on his haunches and sprang away, not toward the bower but back into the mountains. His pads left a trace of red on pale stone.

Rhenna lifted her hand to her right cheek. Her fingers came away washed in crimson. She fell to her knees.

“Sister!” Keleneo stumbled toward her, tripping over the shift in her haste. “Rhenna—”

Calm settled over Rhenna, the peace that was said to come to a warrior before death. But she would not die from such a wound. Nor from what must follow.

“Keli,” she said, “we should not speak. Go back.”

“To that?” She knelt before Rhenna and grasped her bloodied hands. “Your face—oh, Rhenna, your face!”

Rhenna struggled to her feet, pulling her sister with her. “Go back. He will return. I must go … home.”

The weeping stopped. Keleneo gripped Rhenna’s arms, her lovely features twisted in dread. “They will punish you.”

“But not you, Keli.” Rhenna felt blood pooling under her jaw and trickling beneath her collar, thick and warm. “They’ll never know we met.”

“I can’t leave you—”

Rhenna took a deliberate step away. “Mother’s Blessing, Keleneo. Forgive me.”

Keleneo wept silently as Rhenna picked her way down the trail, half-blinded by the blood. She let it spill unhindered and unheeded over the front of her shirt and jacket.

The devas had lied. They had mocked her with their inscrutable promises, but in the end they had made their meaning clear enough.

Rhenna came to the boundary stone with no memory of how she had traveled there. Her weapons lay untouched. She knelt beside the bearskin and waited.

Just at sunset a girl-child came to the Place of the Chosen, bearing flowers in memory of one who had gone. She saw Rhenna’s face and let the bundle fall. Then she ran back to the village as fast as her skinny foal’s legs would carry her.

Sun set. The blood dried on Rhenna’s face. When the first flickering blaze of torchlight emerged out of the darkness, Rhenna rose to meet it.

Part I: Shield of the Sky

Chapter One

Rhenna’s scar was throbbing.

She touched it with absent fingers and scanned the horizon. The horses were quiet. Mares grazed contentedly, heads buried in the rich fodder of oat, rye and feather grass that stretched in every direction as far as the eye could see. Foals tested newfound strength and speed against one another. Ears quivered and tails twitched, but none raised the alarm.

Far to the east and west lay the well-guarded borders of the Shield’s Shadow, the land of the Free People. To the north stood the snow-capped peaks of the Shield itself, and to the south …

Rhenna frowned, shifting her weight on Chaimon’s broad back. To the south were the Skudat tribesmen, Hellenish merchants and the empire—barbarians who entered the Shield’s Shadow at their peril. No, there was no danger in the south.

Chaimon stamped and snorted, jingling the tiny bells on his bridle. “Forgive me, my friend,” Rhenna murmured, scratching the gelding between his ears. “I’m restless today.”

Rhenna echoed Chaimon’s snort. For nine years she had watched the herds, far too long to begin starting at shadows. Too wise to regard the dubious warnings of phantoms and memory.

Chaimon jingled his bells again. The mares paused in their grazing, and Rhenna heard the muffled drum of hoofbeats.

A horse and rider galloped out of the tall grass. The girl’s pale hair was bound in the tail of a novice, and her ears were bare of the double-axe studs worn by every initiated Sister.

Rhenna wound her fists in Chaimon’s mane. The Elders had sent someone at last: an apprentice to take under her wing and prepare in the ways of the Sisterhood. The long exile was over.

She swallowed her eagerness and assumed the cool reserve that befitted one of her age and experience. She expected the girl to bring her mount to a decorous halt, but the rider—surely no more than fourteen or fifteen years—charged headlong at Rhenna. Her gelding’s flanks were mottled with sweat. The girl sawed on the reins and fell back into her saddle with an ungainly thump as the horse skidded to a stop.

Rhenna dismounted and took up a warrior’s stance. “What can be worthy of such great haste, Little Sister, that you ignore the good health of your mount?”

The girl braced her hands on her knees and looked down on Rhenna as if she were the elder. Her dark eyes settled firmly, inevitably, on Rhenna’s disfigurement.

“Rhenna-of-the-Scar?”

“I am Rhenna of the Sisterhood,” Rhenna corrected, the bright spark of hope dying in her breast. “Dismount at once.”

With a scowl the girl obeyed. Rhenna moved past her and examined the exhausted horse, running her hands up and down the legs to check for swelling. “You pushed him hard,” she said, “but he should recover if he’s given enough rest.”

“You—” the girl sputtered. “I—”

Rhenna slipped the bit from the gelding’s mouth and unfastened the bridle, tossing it to the girl. “You will care for your mount before you take rest, food or drink. Then we’ll talk about the proper use of horses.”

The girl caught the bridle and glared at Rhenna, thrusting out her narrow chest. Her iron-studded leather coat was at least a size too big. “I have come …” she began, and let out a short, sharp breath. “I was sent to deliver a message from the Elders. You are summoned to Heart of Oaks with your herd, as quickly as you can move it.”

Rhenna stopped halfway to the small tent where she stored her supplies. No apprentice, she thought. Not her task, after all, to break this filly of her bad habits and teach her the folly of arrogance.

“You are summoned to Heart of Oaks,” the girl repeated. “Didn’t you hear?”

Rhenna continued on to the tent, where she collected a brush, a water skin and a shallow bronze vessel. “What is your name?”

“Deri … Derinoe.”

“I heard you well enough, Derinoe. You may begin by watering your horse—lightly—and walking him until he cools. Then you may rub him down and tell me why the Elders have called in the herd.”

Rhenna’s quiet words seemed to diminish a little of the girl’s self-importance, but her lips remained twisted in contempt. She snatched the waterskin and vessel from Rhenna’s hands as if the merest shared touch might corrupt her.

Rhenna left the girl to her work, mounted Chaimon and rode a circuit of the herd, turning Derinoe’s message about in her mind. Never had she been ordered to deliver a herd to Heart of Oaks. When yearling foals were ready to leave their dams, warriors came to take them away for first training. Healers journeyed across the steppe from pasture to pasture, caring for ill or injured beasts. Once a year the animals were tallied, stallions exchanged, bloodlines recorded. The herds remained free except in the harshest winters or in times of severe drought.

Rhenna’s scar ached with renewed urgency. She completed her ride and loosed Chaimon, who trotted to the new gelding and nuzzled his damp neck. Derinoe had rubbed the animal’s coat until it shone like a bronze mirror.

Rhenna nodded approval and provided Derinoe with fresh spring water and salted meat preserved from her last hunt. She and the girl crouched beside Rhenna’s fire pit, where last night’s ashes still shed some lingering warmth. Derinoe’s eyes sought Rhenna’s scar with unconcealed fascination.

“The stories you’ve heard are undoubtedly true,” Rhenna said softly, “but dishonor is not an illness to be passed by a touch. Eat.”

The girl shivered. Her haughty mask crumpled. “You … you truly saw the Ailuri?”

“What has that to do with your message?”

“I don’t know. Everything is changing.”

“I have not had news in half a year. Tell me.”

Derinoe’s eyes flooded with something very like panic. “The Earthspeakers and Elders are always in the Council Hall or the Sacred Grove. The warriors who guard the eastern and southern borders are being recalled. I have seen them myself. They say it is because of the new attacks on the western border—”

“Attacks?”

“The settlements have been raided. Our people have been taken by men.” She reached toward Rhenna and stopped, her hand flexing in midair. “When has such a thing ever happened before?”

Rhenna couldn’t remember. Every year Earthspeakers rode the borders, invoking the devas to protect the Shield’s Shadow. The man-tribes who coveted more abundant pastures were turned aside by howling winds or fierce storms brought by devas of water and sky. The Sisters of the Axe excelled in the arts of war, but seldom were they forced to test their skills against real enemies.

Now they had been summoned home to defend settlements that should never have been vulnerable to the barbarians.

What had become of the devas?

“How many villages have been attacked?” she asked.

Derinoe scrubbed her face with shaking hands. “They told us … we novices who have not yet won our honors … only what we had to know to gather the herds. No one else could be spared.” She met Rhenna’s gaze. “Do you know, Elder Sister? Do you understand why these things are happening?”

The girl’s naive question slashed at Rhenna’s heart, and she saw herself as she had been nine years ago, tumbling from pride to terror in a single day.

“No,” she said, granting the girl the respect of an equal. “But the answers lie in Heart of Oaks. We’ll rest tonight and take the herd north in the morning. Until then—”

Chaimon jerked up his head. Deri’s mount did the same, and every horse in the herd turned toward the south. Nervous whickers rippled among them; ears flicked back and forth like blades of grass in a high wind.

“What is it?” Derinoe asked. “I see nothing. Is it wolves?”

Rhenna held up her hand. At first she, too, saw nothing. But then a hot wind rose, gusting hair into her face, and a dark smudge appeared on the southern horizon.

“No,” she said slowly. “Not wolves.”

The smudge rose higher, altering its shape with each passing moment. No cloud had ever taken such a form, nor moved so swiftly.

“It must be a storm,” Derinoe offered. She meant one of the black storms that blew out of the southeast, driving hot, dry winds into the steppe. But Rhenna always knew when they were coming.

“Birds,” she said, startled by her own certainty.

Birds. A massive flock of them, greater than any Rhenna had seen.

“I don’t understand,” Derinoe said. “All the birds that winter in the south have already passed over our land.”

She was right; Rhenna had watched them fly overhead by the hundreds in early spring. This was not the same. The mass grew ever larger, accompanied by shrieks and the whirring of myriad wings. The horses bunched, lunging and biting.

Rhenna leaped onto Chaimon’s back. “Ride to the flank, Derinoe” she said. “Keep the horses together, whatever happens.”

Derinoe caught her nervous gelding, mounted and circled to the opposite side of the herd. The flock cast its own shadow, clattering like a hailstorm. Individual birds darted in and out, smashing into their fellows. Fragile shapes plummeted to shatter on the ground. The air was rank with the smell of excrement. A steppe eagle, king of the sky, dove screaming out of the cloud’s relentless path.

Rhenna seldom sang to her horses, for she had no gift for music. Now she reached into memory and found a chant the oldest warriors sometimes used to quiet restive herds. She raised her voice above the birds’ dissonant cries.

The leading edge of the shadow raced across the plain. Rodents and insects boiled up from the grass under the horses’ feet. A single brown bird, no bigger than a sparrow, darted past Rhenna’s ear.

Chaimon trembled. Rhenna used her knife to cut a long strip of cloth from her sleeve and secured it over the horse’s eyes.

Then the wave hit. A clap of thunder deafened her, and a blast of hot air threatened to peel the skin from her face. She called out to Derinoe, but her voice was lost in the clamor of panicked horses and the shrilling of the flock.

Light vanished. Feathers fell like rain, covering the horses’s backs and filling Rhenna’s mouth. Tiny bodies thumped into her padded jacket and tumbled under Chaimon’s hooves. Working blindly, Rhenna tore another strip from her shirtsleeve and tied it over her mouth and nose. The stench was unbearable. And the cries—they were like those of lost souls condemned to endless torment in the Southerners’ pitiless underworld.

Time lost its meaning. If the sun still warmed the earth, Rhenna had no sense of it. She murmured in Chaimon’s ear, praying that none of the herd would be lost.

The devas should have stopped such an abomination before it crossed into the lands of the Free People.

“Rhenna?”

Derinoe’s’s voice was faint, but it was proof that she was alive. Rhenna opened her eyes. Weak shafts of sunlight danced in the tiny spaces between beating wings. The cloud was breaking up, birds scattering to east and west as the largest portion surged ever northward.

Chaimon blew feathers from his nostrils. Rhenna removed her makeshift scarf. Derinoe hunched over her gelding’s back a hundred paces distant. She seemed unhurt. Rhenna turned anxiously to the herd.

Death had followed in the wake of the flock’s passage. Thousands of small brown carcasses covered the grass, but not a single horse had been lost. A few had sustained small injuries and many trembled from the shock. They behaved much the same after a particularly violent thunderstorm.

Thunderstorms were natural, born of earth and sky. There was nothing natural about the birds.

“It was an omen,” Derinoe said, riding up beside her. The girl’s eyes were strange and staring, her cheek streaked with blood as if she had faced her first battle. “The devas are angry.”

Rhenna’s laugh escaped before she could silence it. Derinoe swung upon her with a zealot’s glare.

“You mock them,” she hissed. “I heard …I heard them say that the devas never forgave what you did. You brought this curse upon us.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” Rhenna said. “But the horses need our care, and there’s no use bewailing what can’t be changed.”

Derinoe deflated like a pierced waterskin, wincing as she moved her left shoulder. Over her protests, Rhenna sat the child down and made a thorough examination. Derinoe set her jaw and refused to show any sign of discomfort. A warrior didn’t weep in the face of pain.

Just as a warrior didn’t question, and never dreamed.

Rhenna returned Derinoe’s shirt and remembered how to smile. “Only a pull,” she said. “Try not to use it overmuch, and it’ll work itself out in time. I’ll see to the horses.”

Not greatly to her surprise, Derinoe disregarded her advice and insisted on helping to salve cuts and bind bruised legs. After the worst of the injuries had been tended, she and Rhenna gathered the herd. They moved at a slow pace to fresh pasture two leagues from the path of the birds. The horses forgot their fear and settled to graze and rest, comforting one another with gentle nudges.

Derinoe fell into a deep sleep as soon as her head touched her blanket. Rhenna tended the fire, rising occasionally to check on the horses. Only the small, ordinary sounds of dark-loving creatures broke the tranquility. The night brought its own kind of peace that erased the day’s horror, turning it into a dream without substance.

She lay back on her blanket and closed her eyes, dozing in the half-sleep she had adopted over the years of solitude. If evil came again she would know, and be ready….

Chaimon’s soft lips brushed Rhenna’s forehead. She snatched at her axe and sprang to her feet. The smell of dawn was in the air, and Rhenna realized she had slept far more soundly than she’d intended. Derinoe lay still, one arm flung over her face.

Rhenna sheathed her axe and leaned her head against Chaimon’s. “You kept my watch for me, old friend.”

The gelding’s eyes glinted with secret wisdom. Slowly he turned about, facing north, and bobbed his head.

“Yes, home. Heart of Oaks.” The place she had longed to go, under any circumstances but these. “Only a few days—”

She broke off, feeling a sudden puff of wind on her face. It was not the hot gust from the south that had presaged the birds; it came from the north and west, from the forest and the outlying settlements of the Free People.

Chaimon nickered. The other horses stirred, a faint rustling and shifting of powerful bodies. Rhenna’s scar caught fire. Not so much as a breeze fluttered the edge of Derinoe’s blankets. But a mass of air lifted from the ground at Rhenna’s feet, wound between her legs and lapped at her fingertips like an affectionate hound.

She knew those winds as she knew her own dishonor. Nine years ago they had befriended an ignorant child, stroking and caressing and feeding her naive pride. They had made many promises—oh, not in mortal words, but in a tongue well-known to the ambitious hearts of rebellious young girls with forbidden dreams.

They had led her to the very edge of ruin and let her fall.

“I do not hear you,” she whispered.

Chaimon stretched his neck and whinnied. The wind clung to Rhenna, dancing about her head, teasing her hair loose with a Sister’s license.

“I will not.”

Threadlike currents of air worked inside Rhenna’s jacket, under her shirt, shivered along her skin. The wind knew her more intimately than any lover. Whorls and eddies curled around her neck and tugged at her lobes, set up a deep humming in the bronze of her earstuds.

Come. You are Chosen.

Rhenna covered her ears with her hands. “Be silent!”

The wind mocked her, lifting Chaimon’s mane so that it stood almost erect. Rhenna crouched beside the fire and stabbed viciously at the embers. Abruptly the fire went out, extinguished by a precisely aimed blast of air.

She threw down the stick and stood, legs braced to face her enemy. “You have had your way. Let me be!”

Her shout should have been enough to wake the Skudat dead in their burial mounds. Still Derinoe slept. Dust stung Rhenna’s eyes and scoured her cheeks. She felt her way to the tent and knelt to search the pack just inside.

The wind nearly tore the finely woven scarf from her fist. She fought to tie the cloth over her ears and head, knotting the ends so tightly that only a knife-stroke could cut it free.

The air turned still.

Blood. One word, voiceless. It filled Rhenna’s head as if the wind had driven inside her skull.

North. A current rose at Rhenna’s back, pushing at her shoulders. She stiffened her arms to keep her balance. Chaimon reared. Three veteran mares from the herd broke away from the others and came to stand behind her.

North, the wind said. But not to Heart of Oaks.

West.

Rhenna struggled to her feet. It had been many years since she had felt real fear. She remembered what it was to dread the stares of her people. She had often worried for sick horses, and spent sleepless nights tending them with many a desperate prayer.

Derinoe’s message and the coming of the birds had awakened something greater than alarm. But terror—that had not touched her since she had looked into the eyes of an Ailu shapechanger, had felt in her own ravaged flesh the truth of the ancient stories.

She had sworn then, and a hundred times since, never to seek beyond a warrior’s life. But now the devas called to her in portents of blood and death.

She made one last attempt at defiance, turning into the wind. It sealed her eyes shut and stole every breath.

“If I go,” she shouted, “will you let the others pass? Will you protect them on their journey?”

Wind became a breeze again, almost playful. Rhenna yanked her loose hair into a knot at her neck and tied it with a leather cord.

Quickly she chose one of the three mares, a seven-year-old of sound wind and stamina. The breeze murmured approval. Rhenna bridled and saddled Chaimon and the mare and stuffed her saddlepack with provisions, leaving Derinoe the greater part. Sweet spring water filled two fat waterskins, which she secured to her saddle. As an extra precaution she bound her breasts with a thick winding of cloth and tied a leather girdle about her hips to protect her inner parts from the jarring of an extended ride.

The wind had not revealed her destination nor how long it would take to get there. The devas required her to act on faith.

“I will not risk the horses,” she said aloud, tightening girths and examining hooves. “Guide me well.”

Chaimon stamped and butted her chest, eager to run. The first light of dawn had crested the horizon by the time Rhenna was ready. She crouched beside Derinoe and shook her awake. The girl blinked and rubbed her eyes, dismay crossing her face.

“The birds—” she gasped. “Is it my watch?”

“It’s dawn,” Rhenna said. “I have a grave task for you.” She helped the girl to her feet. “Can you handle the herd alone?”

“I … Alone?” Derinoe threw back her shoulders, but the tremor in her lips ruined the effect. “I am to take you to Heart of Oaks—”

“You were to find me and send the herd home. You’ve accomplished the first, and now you will complete your duty.”

“Without you? What of your duty to the Earthspeakers?”

Rhenna abandoned the last remnants of discretion. “The devas … have sent a message.”

“They spoke to you?”

Only another dreamer could lend the question such fearful resonance. The girl needed every encouragement Rhenna could give her now. “As you said, everything is changing. Will you do what must be done?”

“But I … I am not—” Derinoe bit her lip and looked away. “They sent the youngest,” she said in a low voice, “the smallest, the ones who weren’t ready to fight—”

“They sent the strongest and the swiftest,” Rhenna said. She seized Derinoe’s good arm. “You can do this, Little Sister. I’ll teach you what you must know, and the horses will do the rest.”

The girl raised her head, fragile pride creeping back into her eyes. “Where are you going?”

“I must learn—” All at once Rhenna understood why she would go, and why the devas had won. “I need to know if these terrible things are happening because of me.”

Derinoe flushed. “I didn’t … I never meant—”

“I know.” Rhenna touched Derinoe’s sunburned cheek. “Trust in the devas,” she said, filling the declaration with a child’s unquestioning conviction. “Trust in yourself.”

“I am …” The girl clenched her teeth on the word she wouldn’t speak. Afraid.

Rhenna gazed across the steppe, far to the north where the western margin of the Shield melted into the horizon. Fear teaches. Fear keeps you alive. Never forget to be afraid.

“You are strong, my Sister,” she said, clasping Derinoe’s wrist in a warrior’s grip. “Sharpen your axe and bind up your hair. It’s time to become a woman.”

Steppe ponies were neither beautiful nor elegant, but they were built to travel at a steady pace without faltering. Rhenna’s horses proved the worth of their bloodlines that day.

She settled Chaimon into an easy lope that he could maintain for hours at a time. When he began to show signs of stress, she dismounted, walked to cool him, and then mounted the mare. Every few hours she watered both horses and allowed them to graze. By nightfall they had covered thirty leagues.

The wind was ever at her back, pushing north and west. It sighed in her ear as she rubbed down the horses and made her evening camp; it crouched beside her meager fire like a loyal Sister. Rhenna didn’t expect to sleep, but the devas sang to her, and she woke to Chaimon’s gentle nudging just before dawn.

The second day was much like the first, but Rhenna’s sense of urgency doubled. The premonitions of blood and ruin grew stronger with every passing league, yet the Shield of the Sky and the verdant rim of forested hills seemed no nearer.

On the third day both horses were weary and Rhenna swayed in the saddle. Stops for rest grew longer and more frequent. Only at sunset did the distant trees rise from a faint green line on the horizon.

By mid-morning of the fourth day, Rhenna reached the edge of the forest. Open woodland of oak, linden, beech and poplar crept onto the grassland, sheltering birds whose songs echoed from branch to branch. Small cultivated fields appeared among the trees.

Not far now,

Rhenna whispered to the mare, who gamely nickered in answer. Chaimon broke into a trot. Rhenna began to recognize landmarks, stands of ancient oaks and the weblike tracings of streams that reminded her of a childhood visit long ago. Boggy earth gave under the mare’s hooves, releasing the rich scent of fertile soil.

Sun’s Rest, this place was named. The settlements near the western border produced the finest weavings, woodwork and metalwork in the Shield’s Shadow, goods used in trade and to create beauty for the People. But the villagers weren’t fighters; they kept small livestock and raised crops for their own tables. The man-tribes had so long been quiet that few warriors remained in permanent residence.

If Derinoe was right, all that had changed. The border was a mere dozen leagues to the west. Sisters sent to fight would leave clear evidence of their passage.

Rhenna dismounted and found the tracks of many riders moving at a swift pace toward the west. But something seemed amiss. She lifted her head and listened for the sounds of village life, the everyday murmur of women working at looms and forges and in the fields.

Silence. No frantic scurrying of small animals dodging the tread of hooves and human feet; no querulous chatter of sparrows and thrushes in the undergrowth, nor even the hum of insects. No breath of wind stirred the soft hair at Rhenna’s neck or rustled the oak leaves overhead.

Rhenna increased her pace, following a winding and well-worn path through the wood. Snapped branches littered the ground. A chaos of hoofprints trampled the shallow indentations made by the soft boots of artisans.

Trees gave way to a clearing and the first of the pretty wooden houses. Chaimon and the mare stopped and would go no farther. Rhenna continued on alone. She came upon the remains of a fat sow beside the house. A horde of glossy black ravens started up from the nearby pen, circled with raucous cries and returned to their meal.

There were enough bodies to feed a thousand scavengers. Every beast that could not be stolen had been slaughtered and left to rot. Tears leaked from Rhenna’s eyes. She drew her axe and held it ready, though she knew there would be no one to fight.

She knew what she must find.

The women had been herded together in the village green. Some had fallen still locked in embraces, others shielding sisters from attack. A few had bravely faced the enemy; one old woman had died with a goatherd’s staff in her hand. Its tip was bathed in blood.

Rhenna clenched her fingers around the handle of her axe. Her legs carried her past the mounded corpses. She forced herself to enter each lodge or workshop to search for survivors.

All were empty, weavings and woodwork torn and hacked to pieces. Vegetable gardens had been trampled, plants uprooted in an orgy of destruction. The brightly painted door of one lodge stood open as if in cheerful welcome. A raven flew out, struck Rhenna and dodged skyward with a prize of red meat in its beak.

Step by heavy step Rhenna trudged to the doorway. Her body lacked all sensation, but her eyes continued to search, her ears to strain for any sound of life. The scent of corruption smothered her like a storm of ravens’ feathers.

She reached the door. The axe dropped from her fingers.

The children.

Rhenna fell to her knees. Her mouth flooded with the remains of her last scanty meal. Her heart thudded once in her chest and stopped. To breathe was to die.

Oh, the children.

Rhenna flung back her head and wailed. She seized her axe in both hands and ran, stumbling, past the last few houses and into the Sacred Grove.

There were no woman-made boundaries or marks in the earth to show where ordinary woodland ended and the Grove began. Yet Rhenna knew when she crossed the threshold. She had not entered such a place in nine years. Now, as then, it was as if a thousand angry wasps converged upon her body and drove their stings through cloth and leather. Bitter, irrefutable punishment.

And power. Centuries of chants and prayers and invocations saturated the earth under the roots of the venerable trees. It gilded every twig and leaf, infused the very air with the unnameable odors of sanctity. If any villagers had escaped the massacre, they would have fled to this last place of sanctuary.

Rhenna ran blindly for the center of the Grove. Pain ceased as abruptly as it had come. Its absence seemed to have lifted her from her feet, pulled her axe high above her head and dropped her like a child’s wooden doll at the roots of the Mother Tree. Her hands sank into ankle-deep mud.

The ground was red.

They had spilled blood in the Sacred Grove. The Earthspeakers had not stopped them. The devas had remained silent. And the Mother Tree…

Every branch within human reach had been cut or torn or severed by merciless iron. Stripped bark hung like flayed skin from the trunk. The great arched roots were buried knee-deep in skeletal leaves.

Rhenna’s scar became a patch of numbness that spread across her face, into her shoulder and down her arm, until her fingers could no longer grip the handle of her axe. The weapon fell. With a moan, Rhenna felt among the curled leaves and hewn branches. Every sweep uncovered lifeless hands and staring faces.

The axe blade sliced into Rhenna’s palm as she searched the ground. She snatched it up and scrambled from the place of slaughter, leaving a trail of her own blood behind.

Instinct led her to the horses. They flung up their heads with wild eyes, smelling death. Rhenna bound her slashed palm, calmed the animals as best she could and led them upwind from the village, where they would be undisturbed by the stench of smoke and burning flesh. For the span of an hour she composed her thoughts, letting the numbness expand until it made hard, cold lumps of her head and heart. Then she returned to Sun’s Rest.

She didn’t leave again until her work was done. At dawn she saddled the horses and turned toward the west.

The raiders could not be far ahead. Rhenna had seen no Earthspeakers among the dead. The barbarians must have taken prisoners. Captives would slow them. They would never expect an attack from a single warrior.

Rhenna rode out of the woods and kept riding until the vast column of smoke behind her became a pale gray banner tattered by the wind.

Chapter Two

Tahvo of the Samah stopped at the edge of the cliff and looked down, down and down again, past gradually descending hills and into the vast expanse of the valley below. The world she had known all her life—forest and fell, hills and fields of ice—ended there in the Southlands, where men had only a few words for snow.

She shivered and sat on a stone beside a stream. Her shaman’s robe lay heavy and stifling on her shoulders. Not even the eldest and wisest noaiddit, who called the salmon and the reindeer and knew the spirits by name, had ever ventured so far.

They had no need, for all the Samah required lay within their borders. The spirits spoke through the drums, and shamans carried their blessings to the people. Noaiddit healed the sick, forecast weather and sometimes spoke to the dead. A very few could see what was to come.

Tahvo’s visions were different. No other female had been shaman for a thousand seasons. From her birth, her family had kept her apart from the other girls, for she had received the spirit-gifts that should have gone to the stillborn boy who had emerged from the womb before her.

You will be a healer, predicted her grandfather, a great noaidi in his own right. And so she had become. She tended the ill, childbearing women and sometimes the dying. The spirits lent her strength in her work; they were always with her.

But she had never truly understood them. She could not see them or hear their voices or tell one apart from another. She did not summon them to send game to the hunters or keep the heaviest snowfall away from the siida. She had not asked for the visions, yet they visited her instead of more worthy noaiddit. After the fits passed, people looked at her as if she had lost the snow-sense or fallen into madness.

They did not know that the visions had shown her the meaning of an idea for which the Samah had but one word.

Evil.

Tahvo opened her sturdy deerskin pack and carefully pulled her drum from the down padding within. Six years ago, when she had become a woman in fact if not in custom, she had constructed the frame of birch and stretched the reindeer skin she herself had prepared. With alder juice she had painted every mark upon its face: symbols representing each of the four directions, the spirits of Nature, and the three realms of existence.

She had drummed many long nights alone, praying that the spirits might ease this burden. But the answers they put in her heart were as relentless as they were inconceivable.

South.

She put the drum back inside her pack and made sure her small hunting bow was secure in its case. The descent was not difficult, though Tahvo’s boots sometimes slipped on the bare earth and mats of needles. She drank from the cold stream and ate what the spirits placed in her path. The snow disappeared. Trees changed their shapes. Unfamiliar birds remarked upon the passage of a stranger.

The next day Tahvo came to another cliff, this one surmounted by a waterfall. At its foot, all was green as far as the eye could see, rolling plain laced with a hundred streams. On the plain lay what the traders called a town, far bigger than any siida. The town’s high walls rose from an empty space where trees had been cut to the ground and soil overturned with tools of iron.

To that strange and terrible place she must go.

Stones and gnarled roots gave Tahvo purchase to descend the steep face of the cliff. She paused on a small ledge halfway down, clinging to the rock as she drank from her waterskin. Spray from the waterfall splashed her face, but by the time she had reached the bottom she longed for the kiss of a gentle snow.

All she saw was endless grass. The strength went out of her legs. She lost her balance and fell at the base of the cliff, struggling against the sudden, crushing weight of fear.

For as long as she could remember, since long before the visions came, Tahvo had perceived the spirits as a formless, blended presence inside her, sure as the rising of the sun. Now she felt nothing. The spirits had melted away with the snows, leaving a great void in her chest.

They had abandoned her. But that was not possible. The spirits had set her on this path. Why had they chosen one so blind to receive their warning?

She closed her eyes, remembering everything Grandfather had tried to teach her. Samah move according to the seasons, but most spirits belong to a place, just as each has its element—earth, air, water or fire. Some, like the winds, range across the open fells. Others reside in a single stand of pines, or in the smallest of ponds. Yet even we who name them do not know all the spirits of the Samah, far less of those beyond.

Noaiddit never had cause to call upon spirits outside Samah lands. But the traders invoked what they called their “gods” even when they were far from home.

Tahvo’s heart beat fast with hope. She hurried to gather a bundle of twigs and leaves fallen from the top of the cliff and used her flints to coax a small flame. Then she removed her drum, the pouch of precious dreambark and one of the small bronze bowls from her pack. She crumbled a little of the dreambark into the bowl and set it on the fire.

The bark burned with a pungent, intoxicating odor. Tahvo took a deep breath of the smoke. With each inhalation came the blissful release of fear, melting like snowflakes on a reindeer’s back. The green expanse of grass broke into pieces that floated up into the sky. The whole world shrank to the size of a pebble.

Tahvo began to sing, tapping the rim of the drum in time to the words. The spirits answered. She could not see or count or name the beings that gathered around her, but she felt at once that they were not those she had known. The skin on her face prickled with moisture, a cooling breath to counter her weariness. The air hummed. She dropped her hands into the grass and felt the life flowing between her fingers, part of an endless web that extended on every side as far as her imagination could reach.

Then the vision came, and she was home again. A stream flowed out of the forest, pure and swift beneath its covering of ice. The spirits of these waters knew the call of the noaiddit, but the stream did not belong to a single country or people. It journeyed ever south, fed by other streams, blessed by innumerable spirits until it became a great river in lands that had never known the Samah tongue.

Tahvo was part of that mighty river. It rushed through and around her, lifting her in a loving mother’s arms. She glimpsed wide lakes and mountains of fire, vast waterless plains and forests thick with leaves like green leather. Spirits lived on every shore the river touched. They spoke to each other, but still Tahvo did not understand their words.

Her ignorance did not trouble her. She wished the wondrous vision to last forever. It did not. Suddenly she was back in the forest, standing on the bank of the little stream. The ice cracked and dissolved. Hideous red stones, twisted like animal entrails, appeared in the water, turning it the color of blood. Roiling bubbles surged up around the misshapen lumps. Branches bent low over the stream caught fire. Flames leaped from tree to tree.

The forest burned.

Tahvo gasped for breath, running toward the siida. The flames turned her away. Only the cliff offered escape.

She reached the cliff’s edge and leaped.

The vision released her before she hit the ground. She exhaled the last of the smoke and opened her eyes, trembling with relief. Sweet water whispered in the pool beside her. She made a cup of her hands and rinsed the foul taste from her mouth.

That was when she felt the spirit in the pool. She snatched back her hands, belatedly remembering the prayer she had forgotten to offer. She reached dizzily for the cliff wall at her back and felt the life within it, touched the earth and knew that it teemed with spirits who blessed the soil with richness and danced to the drumming of the world’s heart.

Tears of joy blurred Tahvo’s sight and cleansed the terror of the vision from her mind. The spirits had not deserted her. They were no longer a vague, undefinable presence in her mind. She still could not name them or summon their powers, but they had granted her what she had never possessed: the ability to recognize them not only in the work of healing but in all of nature’s elements.

She was not alone, and she knew she never would be, as long as she heeded the spirits’ message.

South.

Tahvo stretched cramped muscles, washed the bowl and returned it to the pack. She strapped the drum against her chest, concealing it beneath her coat without knowing why she did so.

She could not reckon the distance to the town; the valley stretched on and on to faraway southern mountains whose white peaks gleamed like teeth against the sky. She crossed creeks and rivers, removing her boots to wade through currents still icy with the memory of winter. Wildflowers thrust above the grass, bowing as she passed. Large hoofed animals with sharply pointed horns—cattle, the traders called them—paused in their grazing to stare at Tahvo with limpid eyes.

The air continued to warm. Tahvo longed to take off her coat, but a noaidi never removed it except in times of direst need. A spirit-wind spiraled about her head and brushed hair from her hot face and neck.

The walls of the village rose higher and more ominous with every hour. Men and women, some afoot and some mounted on the beasts called “horses,” converged about the open gate.

Tahvo’s heart beat very fast. She fastened her coat and set off for the gate. The grass gave way to a path bordered by fields of stubble and shoots of spring grain. Beyond the fields stood rows of tents and tables spread with goods for trade. The stench of many bodies, animal dung and food overwhelmed the scent of flowers. Naked children darted between the tables. Bright clothing wove a constantly moving pattern impossible for the eye to unravel.

Men argued in tongues Tahvo had never heard before. Their words rattled about inside her head.

“Ah,” a voice said at her elbow, “a newcomer to our fair village.”

Tahvo turned about to face the speaker. He was taller than Tahvo, with dark eyes and hair on his face cut to a point at his chin. At his belt hung a knife in a sheathe of tanned animal skin.

“Of course you don’t understand me,” the man said. He looked Tahvo up and down. “From the far North, are you? You’ll be needing a friend here, and I’ve always been too soft-hearted.” He smiled with all his teeth. “I am called Beytill.”

Tahvo returned the man’s smile but did not answer. His mouth moved out of step with his words, yet somehow she made sense of what he said. She gave silent thanks for yet another unexpected gift of the spirits.

Beytill rested his hand on Tahvo’s arm, running his hands over the thick fur. “That’s a fine coat, my friend, a very fine coat indeed. A handsome bow, as well. What else have you to trade, I wonder?” He clamped his arm around Tahvo’s shoulders and pulled her through the gate.

Immediately Tahvo’s sense of the spirits dimmed. They did not come within these walls, but she had no doubt that they intended her to enter. Soon they would reveal their purpose.

The village dwellings were built of wood, with roofs woven of dried grasses. Some had open doorways through which many people came and went. Even in this warmth, the women who lingered outside wore too few garments to protect their bodies. Men bore long knives hung from their waists, blades useless for hunting or carving.

The traders carried such weapons. They told tales of war and warriors in the south, of blood shed for reasons the Samah could barely comprehend.

“Nervous, are we?” Beytill said. “I’ll wager you’ve never seen a civilized town. A good draft of beer will set you to rights.” He dragged Tahvo toward a house where men stood about drinking from thin metal cups and earthenware bowls. Angry voices escaped the dim interior.

Tahvo braced her knees and stood firm, searching for anything familiar. The high-pitched laughter of children drew her back toward the wall.

A moderate crowd of onlookers had formed a loose circle about a man in a long dark robe of deep red. His face was shadowed by a hood, but his long fingers flashed in motions too swift for the eye to follow, tossing bright objects in circles around his head and shoulders. Children laughed and their elders applauded as he caught the objects one-handed, flourished his wide sleeve and presented a ball of flame in his cupped palms.

The flame looked real. The man might be a noaidi of these people, but Tahvo could not sense the presence of any spirit to help him make such magic.

“The mage interests you, does he?” Beytill said behind her. “I know him. Come.” He pushed his way through the crowd until he and Tahvo stood in the front ranks. The noaidi—mage—had already begun another exhibition. He selected a girl child from the audience and stood her before him, resting his hands on her shoulders. She stared up at him, mouth agape. He shaped the air over the child’s head, twisting his hands in sinuous gestures like writhing serpents.

The display made Tahvo shiver. She saw no illness or injury in the child that required a healer’s attention, and she knew this man was not a healer. Nor was he a shaman in the Samah way. She stared at the black hollow of his hood and suddenly recognized what seemed so wrong.

It was not merely the absence of spirits behind the dark man’s working, or even the faint stench of rot he gave off with every breath. His cloak sucked all light into its red folds and snuffed it out, leaving only a kind of shadow where he stood—a void where no living thing could exist.

The mage flung his arm toward the sky, briefly parting the edges of his robe where hood met collar. A small object swung out from a cord around his neck. He smoothed his cloak with an almost imperceptible motion, but not before Tahvo glimpsed the gold-mounted shard of faceted red stone.

She could not move even to snatch the child away.

The onlookers gasped. Fists and elbows jostled Tahvo as people shifted for a better view. The child was enveloped in a feverish radiance cast from the mage’s widespread fingers.

And the child grew. She began to stretch, pinned like a hide on a frame of fire, bones visible through skin. The scraps of her thin clothing melted away. Hips widened, waist narrowed, and her flat chest rounded into the heavy breasts of full womanhood. Her parted lips grew lush and moist. When the fire receded, the child was a child no longer.

eytill and other men stamped and whistled. The mage stepped back, hands poised as if waiting for a signal. A woman darted out of the crowd and began to wail, shaking her fists at the hooded man.

The mage flicked his fingers. The naked woman vanished, and the child fell, ashen-faced, into her weeping mother’s arms.

Tahvo swayed, lost in a dream not of the spirits’ making. Here was the evil. Here was what she had been sent to find….

“See what you can do with this one!” Beytill cried, and gave Tahvo a great push toward the center of the circle. The people laughed and jeered, passing her one to another, loosening the fastenings of her coat. She folded her arms against her chest and stumbled to a halt before the mage.

He raised his head. His features were lost in the depths of shadow, but his eyes glowed like coals. He extended a hand, and Tahvo saw that his knuckles were knotted and swollen above the long fingers.

“Woman,” he said in a low, grating voice. “What are you?”

“Woman!” Beytill cried. “That’s a female?”

The curious crowd surged forward. Tahvo’s heart slammed the inside of her ribs. The deerskin straps that bound the sacred drum to her chest grew tighter and tighter, threatening to stop the air in her lungs.

“A savage from the Northern wastes!” someone shouted. “Who can tell the difference?”

Beytill waded to Tahvo’s side and seized the shoulder of her coat, yanking it open. The drum was exposed, pale as bone laid bare by the slash of a knife.

“What’s this?” Beytill demanded.

Tahvo felt the hooded man’s gaze fix on the drum. But it was Beytill who plucked at the straps, Beytill who snapped his hand away with a yelp when his flesh turned blue with countless needle-sharp crystals of ice.

Tahvo cried out in shock. A chorus of shouts washed over her, twice as loud as the roar of meltwater racing down from the mountains in spring. Fingers pulled at the thongs and pendants on her coat. Spittle sprayed her cheek. She turned the drum in her arms so that she could tap the rim with two fingers, knelt, closed her eyes and forced all awareness of the villagers from her thoughts.

Help me.

A wind blew out of the North, carrying the scent of snow. Voices raised in anger held a new note of confusion. And fear.

From the place where Tahvo knelt to the village gates spread a wide path of ice. Upon the path trod a white wolf, bigger than any wolf of the forest or fells. It sat on its haunches halfway to the crowd and yawned, revealing long and very pointed teeth.

A spirit-beast. Tahvo had never seen such a creature before, let alone attempted to summon one. She gave thanks and looked for the dark mage. He stood apart from the others, hands tucked into the wide sleeves of his cloak. Beytill pulled the knife from the sheathe at his waist and lunged at Tahvo.

Between one moment and the next the wolf crossed the path and leaped, jaws seizing Beytill’s wrist. Beytill screamed. His blade clattered to the ground and broke into a thousand icy shards. The crowd scattered, fleeing Tahvo and the wolf. The mage disappeared.

Warm fur brushed Tahvo’s fingers. She met the wolf’s blue eyes with confusion and gratitude. He had chosen to make himself visible to her eyes, but he was as unlike the valley spirits as Beytill was unlike Grandfather. Samah spirits never turned their powers against men.

“Who are you?” she asked silently, not expecting an answer.

She thought she heard laughter. “I am Slahtti.”

Sleet. Tahvo trembled, overwhelmed by the wonder of his voice in her mind. “Is this the place I was meant to find?” she asked. “Is this the source of the evil visions?”

“You must save your people.”

Too many questions thickened her tongue. “How?” she begged, clutching his mane in disregard of proper respect. “Who will hurt them? This man…this mage with the red stone? Why—?”

The wolf pulled free and shook himself from nose to tail. “Come,” he commanded. His breath blew out in a stream of mist that formed a new path of ice in the very air itself. Teeth closed gently on Tahvo’s hand.

That was all Tahvo knew until she woke in a bed of wildflowers, her pack beside her and the drum resting on her chest. A handful of snowflakes kissed her face. The walled village was a dark blotch on the northern horizon. White-capped mountains bit the southern sky.

The spirit-wolf had borne Tahvo a day’s walk in an instant. He had saved her life, but he was gone. Her questions remained unanswered.

Surely the spirits had meant her to enter the town and witness the evil within it—Beytill’s treachery, the cruelty of the people and, most of all, the dark shaman’s magic. The threat to the Samah must lie there, if she could only recognize it….

The new vision struck swiftly. This one began with fire. Devouring flame spewed out of the ground like the effluence of some foul and incurable illness. Tahvo saw the exotic lands the valley spirits had shown her—rain forests and deserts, plains and mountains crowned with clouds—reduced to black ash. Vast dark seas boiled and roared.

And there were people…people in numbers beyond counting, pale and dark, short and tall, clothed in furs or naked as babes. They ravaged what remained of the land. They killed for the sake of killing, tearing at each other and hurling themselves into the searing holocaust.

Of spirits there were none. Every one had fled, forsaking the world to this evil thing men had done. But other beings rose out of the desolation, towering above the people who scurried under their feet: eight entities, neither human nor spirit, clad in metal that devoured all light. Each pair of massive hands bore a blade of crimson iron, and each face was hidden behind a mask of bloodred crystal.

Their will was the complete denial of creation, their power that of the spirits twisted into hatred for life itself. They had but a single name.

The Stone God.

Tahvo’s body seized in a spine-snapping arc, threatening to burst lungs and heart. Her eyes rolled back, yet she could see.

Above the southern mountains rose a red glow, a grotesque reflection of the Sky Veil that shone in Northern skies. A bloated sun rose, casting fingers of murky light across the plain. From its center exploded a hail of stones—red stones, tossed wide as if by the hands of the metal giants themselves.

Most of the stones struck earth behind the mountains. One tiny chip shot over Tahvo’s head and swooped like a hawk toward the distant town. The wooden walls blazed with mordant fire. Children screamed. Sparks shot up to become new stones that flew, swift and deadly, toward the home of the Samah.

Save your people, Slahtti said. Not only the Samah, so isolated in their haven of fell and forest, but the traders and the townsfolk, those who dwelt in the waterless barrens and beside the great sea. All the people in the world.

Tahvo heaved in the grass until she had brought up what little she had eaten that morning. She rinsed her mouth with water from a nearby spring, tucked the drum in her pack and got to her feet.

The spirits had spoken. They had given Tahvo great gifts to aid in the work to come, but the town and its evil were a warning. She still had far to go.

She hitched the pack higher on her shoulders and took the first step.