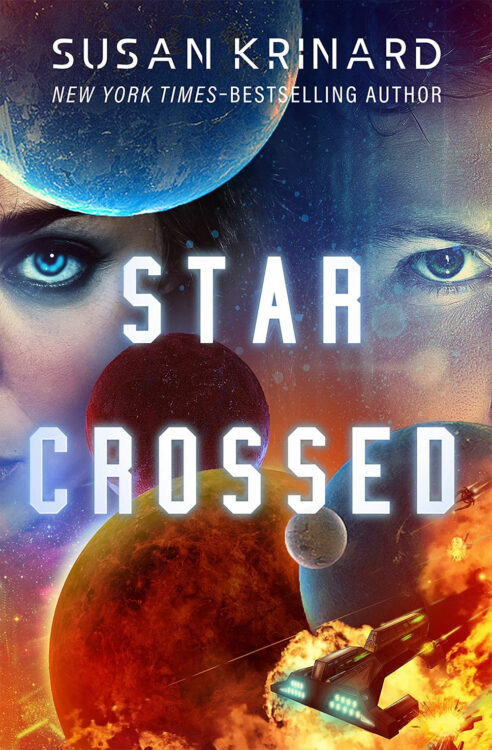

Star-Crossed

A futuristic romance “filled with nonstop action and exhilarating passion” from the New York Times–bestselling author of the Midgard and Fane series (Literary Times).

When Lady Ariane Burke-Marchand’s brother is killed, a Kalian refugee named Rook Galloway is suspected of the murder. Though Ariane once loved Rook from afar, she now turns her back on him and stokes the flames of hatred between the Marchands and Kalians.

Eight years later, Ariane goes to confront Rook, who is serving out his prison sentence on a brutal planet. Caught in a whirlwind of political turmoil and mutual mistrust, Ariane becomes Rook’s pawn in a desperate game of vengeance. But the desire that once stirred their souls cannot be contained, and Ariane and Rook will find themselves fighting for each other—and the truth.

The book has been published previously with Bantam in 1995.

Read an Excerpt

“I’d advise against it, Lady Ariane,” the warden said, his hands clasped behind his back. “The workstations have minimal security. Out there we don’t need it. But it’s not set up for visitors. The men out there—”

Ariane smiled patiently as he shook his head, but her thoughts were far from this small, cluttered office so removed from the harshness of the Tantalan wilderness. Out there, he said. Out there where prisoners from all the worlds of the League labored to fill their sentences, and died if they were lucky.

Out there, where Rook Galloway was condemned to a life of endless misery. She’d read about the prison world before she’d come to drop off the shipments of drugs and electronic equipment from Espérance; Tantalus was a convenient place to dispose of criminals who were judged to be beyond rehabilitation.

Like the murderer of her brother.

Eight years ago. Ariane turned to look out the tinted window at the jungle. Eight years ago she’d seen the Kalian condemned to death, only to have his sentence commuted to life imprisonment on Tantalus. The League had been responsible for that. Grand-père had wanted him dead. But the League did not approve of such barbaric practices, and the Patriarch had bowed to the pressure.

Ten Kalians had been sent to Tantalus. Only one was still alive, according to the records the d’Artagnan‘s computer had accessed.

Rook Galloway.

In eight years Ariane had come to terms with her grief. She thought the bitterness and hatred were finally behind her. It should have been possible to forget Galloway and let him rot on Tantalus.

In two Espérancian weeks she would be meeting Wynn on the League space station Agora. In two weeks she would be giving up her freedom, putting behind her the three glorious years in space piloting a swift courier ship between Espérance and her family’s business interests throughout the League. And she would go home to become Wynn’s bride, confined to a sedate life in Lumière, no longer a rebellious girl but a woman of the Elite, bred to bear heirs and keep her husband’s honor as she’d once kept her own.

There would be no room for dreams or regrets.

Once she had dreamed of exploring the stars. Finding new worlds, free to do as she chose. If Jacques hadn’t died…

Ariane shook her head. She had come to terms with the loss of freedom, of everything she had become. But she had not been able to forget the Kalian who had made her understand the meaning of sorrow.

She could still remember his face. Remember the way he had looked at her, pleading, begging her for something she couldn’t give. And during the trial, when he’d testified—because Grand-père favored the League ways now—when he’d had a chance to defend himself. And had claimed innocence.

Innocence. Ariane closed her eyes. He could not be innocent. And yet when she had been sent with a shipment to Tantalus, she had found herself unable to leave.

Not until she’d seen him. One last time.

She turned to face the warden. “I understand the dangers, but I must speak to this man. It’s of grave importance.” Fixing him with her most commanding gaze, she played her family’s rank and reputation for all it was worth. Even here the Marchand name was known, and long ago she’d learned how to use the beauty and poise and unconscious authority bestowed by her breeding to get what she wanted.

The warden blinked. “Uh, Lady Ariane, we—”

“Just Ariane, please, Warden Rostov.” She leaned forward, placing her manicured hands flat on his battered desk. “Family business, you understand. I promise I won’t be any trouble.”

Rostov masked a frown without complete success and picked up a comp pad from the desk.

“You know he’s the last one left here. The last Kalian. You’d think they’d have had a better survival rate than”—he coughed behind his free hand—”ordinary humans.”

Ariane suppressed a shudder. The last one. Perhaps the last Kalian in existence. The warden’s voice was casual. How many non-Espérancians had ever seen a Kalian outside of news broadcasts or old litdisks? How many cared that those not condemned in the Warren riots had been lost on their way to Agora in a Marchand cargo ship?

“I know,” Ariane answered softly. “It’s because of this that it’s — even more vital I speak to him.”

Pursing his lips, the warden regarded her for a moment longer before slapping the pad back on the desk. “Very well, Lady Marchand. I’ll provide you with a list of rules and regulations that will make your journey as safe as possible. And I’ll have to ask you to sign a release–” He shrugged apologetically.

“Whatever is required,” she put in.

“I’ll have Hudson here escort you,” he said, nodding at the tall young guard who stood silently just inside the doorway. He checked his watch. “Early afternoon now. It may take me a few hours to arrange transport—”

“I have my own—a Dragonfly. Very fast and safe,” she added quickly when he seemed about to object.

But the warden was well aware of the capabilities of Espérance’s Dragonfly helijets, far more reliable than anything Tantalus could provide. And he must know her capabilities as a pilot; no novice could handle a starship like the d’Artagnan. After a moment he nodded.

“If you’ll return to the lounge, Lady Ariane. I’ll see that instructions and the release are brought to you there within the next hour. Good luck.”

His attention was already elsewhere when she left the office. Ariane smiled wryly. If the male warden of an isolated prison world could dismiss her so quickly, she must be losing her touch.

Such idle thoughts of flirtation were all she had. She would go to Wynn a virgin bride, according to all the ancient customs of the Elite.

Her smile faded. She couldn’t go to Wynn at all, couldn’t lay the past to rest, until one last question was answered. Until she could erase the haunting memory of Rook Galloway’s face.

And then, for her family’s sacred honor and in Jacques’s memory, she would give up her freedom forever.

#

The young guard pointed down at the jungle through the Dragonfly’s canopy. “There, Lady Ariane.”

She eased the helijet into a turn as she examined the smudge of lighter green where a clearing had been hacked out of the jungle. Beyond a jumble of low buildings there were open fields, and the tiny shapes of men laboring in them.

Hudson whistled through his teeth “First time I’ve been out here, Lady Ariane,” he said. “First six months of duty they’ve kept me back at Base. They only send the veterans out here, they said.” He gave an uneasy chuckle. “I had my doubts about getting into space by contracting to Tantalus — but back on Liberty it takes a lot of credits to get the training.” He sighed wistfully. “I sure miss home, though. Here I can earn the money to . . .”

Ariane hardly heard the voluble guard’s words. Her attention was fixed on landing the helijet on the small circular landing platform, empty except for one primitive Hummingbird skimmer and a transport that looked due for major servicing. She set the Dragonfly down light as a feather, earning an almost worshipful glance from the young guard.

Galloway was here. Somewhere. Ariane shut off the engines, locked the helijet down, and stared around her.

The heat was sweltering. She could feel her borrowed coverall beginning to stick to her skin, though the warden had assured her it was top of the line for tropical environments.

Raucous noise came from the jungle that pushed in at the rows of barracks and offices, cries and screams that made Ariane shudder.

The records said that the mortality rate here was higher than any on other worlds in the League. Being sent to Tantalus was as good as a death sentence.

Ariane left the helijet and began to walk across the landing pad toward the buildings, Hudson in tow, not surprised that there was no one to meet her. No amenities here, no unnecessary ritual. This was a place of punishment—for the guards, she thought, as much as for the prisoners. Except that the guards got double hazard pay.

Rook Galloway was a Kalian. The Kalian prisoners here had had an advantage over their ordinary human peers: they’d come from a world even harsher than this one. Kali. But now only one Kalian remained.

Stripping already wet hair from her forehead and gathering it into a twist at the base of her neck, Ariane let the young guard take the lead as they arrived at the unadorned building designated for prison personnel. Hudson pressed his badge against the IDlock, and the triple doors slid open one by one to admit them.

The deputy warden for the workstation rose to greet her, his expression harried and almost hostile. The sporadic hum of an overworked cooler stuttered somewhere behind his desk.

“Lady Ariane?” he said sharply. “We didn’t expect you so soon.”

She smiled at him. “I’m sorry for the inconvenience. I assumed the warden explained the reason I’m here . . . .”

“Yes. Yes, he did. But if I had my way, I’d–” He shut his mouth with a snap and took a deep breath. “The man you want to see is being brought in from the fields.” He looked her up and down; Ariane could see the way he cataloged her and considered her origins. “If you’re willing to wait, we can have him cleaned up first, arrange the proper security. We don’t often have—visitors—here. And for this prisoner, in particular–” He frowned. “We’ll set up a force shield for the interview. You’ll be perfectly safe. I’ll assign guards to—”

“That won’t be necessary.” Fool, Ariane told herself. Take all the security he’s willing to give. But she only shook her head. “I haven’t much time. I’ll see him as soon as he arrives.” Her smile took the edge off her words, but the deputy warden couldn’t mistake the command. He scowled and shrugged.

“You signed the release, Lady Ariane. He’ll be secured with manacles, in any case.” He turned away to make a quick call, spat a series of orders, and confronted her again, briefly eyeing Hudson over her shoulder. “Come this way.”

The place was bleak enough. Cold gray walls, featureless corridors. As a prison should be, she thought. But she imagined herself trapped there, committed to some tiny cell at the end of each day’s hard labor, knowing she would go mad. She had always been terrified of confinement.

She shuddered. Here there could be no future, no escape.

No hope.

The deputy warden took her into a bare room with a single table and several hard-backed chairs. There were no windows looking out into the jungle. The room stank of fear; Ariane could feel it. As she’d once felt fear and pain and chaos on a night eight years ago on a world light-years away.

Hudson and three other guards ranged behind her as she sat stiffly in the chair at one end of the table. The far door hissed open.

She saw him almost immediately, half a head taller than his guards—dark hair matted and damp, the black slash of eyebrows above eyes fixed on the ground.

And then his guards moved aside and he looked up. The guards, the room, the world outside vanished. Ariane opened her mouth and found herself gone mute.

He was changed. Horribly changed.

The handsome young man she had been infatuated with eight years ago might never have existed. There were scars marking his face, some light and faded, others new. The high cheekbones and strong jaw were sculpted in harsh relief, as if every last ounce of softness had been burned away. His mouth was set in a grim and bitter line. His black hair flowed down to his shoulders, drawn back loosely with a scrap of rag. He looked like a savage.

But his eyes… Ariane could not look away from his eyes. They were like burning coals, red-hot metal, utterly inhuman.

She saw the change in those eyes as recognition came, reflecting eight years’ metamorphosis from the girl she had been.

She saw him remember, relive it all as she had done so many times since the day of Jacques’s death. And a face that had been hard grew implacable.

“Marchand,” he said, his voice a hoarse rumble. Sleek, powerful muscle bunched under the sweat-soaked work clothes that clung like a second skin. He stopped where he was, resisting the guards who pushed him toward the empty chair at the end of the table.

One of the guards behind him removed a black rod from his belt and lightly touched Rook’s shoulder. Ariane flinched from the pain she could not truly feel, watched the shock course through Rook’s body, a faint tightening of his muscles, a tic set to jumping in his cheek.

Rook’s face revealed nothing as they shoved him forward again and pushed him down in the chair, fixing adamantium cables from his manacled wrists to bolts in the floor. His eyes never left Ariane’s. Runnels of perspiration dripped from his jaw to the table in a slow maddening rhythm.

“Lady Ariane,” the deputy warden said behind her, clearing his throat. “I suggest you—”

“Leave us alone,” she said.

The guards looked at each other. The one with the black rod fingered it as if he hoped for another opportunity to use it.

“Impossible,” the warden snapped. “We can’t leave you with this—”

“I signed your damned release.” Ariane got to her feet, turned and stared at the warden coldly. “Now, please—go. I’ll call you when I’m finished.”

Perhaps if the warden had had any idea of how the Patriarch of the Marchand on Espérance would react to knowing his great-granddaughter was alone with a murderous Kalian, he would never have agreed. But as it was, he merely favored her with another shrug and motioned for the guards to leave. They filed out reluctantly, Hudson the last to go, his open young face deeply concerned.

Ariane sucked in a deep, ragged breath and turned slowly from the door. Turned to face her nemesis.

“You know who I am,” she said, bracing her hands on the tabletop.

For a moment she thought he wouldn’t speak at all. “I have reason to remember,” he said at last, his voice unnervingly even. “When they told me I had a visitor, I never expected such an honor.”

In the very flatness of the words she heard a subtle mockery. The man condemned for killing her brother looked at her without remorse.

Ariane felt as though she were the one being judged.

“What did Kalians ever know of honor?” she said under her breath.

For the first time his expression changed, a slight lift at the corner of his grim-set mouth. “Eight years ago,” he countered, “we learned the meaning of Marchand honor.”

She clenched her fists on the table, grasping at emotions that threatened to slip out of control. It was harder, much harder to confront him than she had thought it would be. Harder to see him so changed. Harder to be certain of his guilt, when she must be certain….

“Why did you come here, Lady Ariane?”

He moved suddenly, shifting in his chair, and Ariane flinched. Cables hissed, pulled taut, and released again. Copper eyes followed her like a predator’s.

“You see the last Kalian on Tantalus,” he said softly. “The last of those your family sent to rot here.”

Both sickened and fascinated, Ariane let her eyes wander over his body: the lean muscle honed by heavy labor, the scarred face, the red welts of bites and scratches on every centimeter of tanned skin. His words, his eyes, condemned her and what she was, and yet he was the condemned. He was the criminal.

His eyes had narrowed to slits when she met them again. “Your Espérancian punishment was very thorough, Lady Ariane.” He leaned closer, almost whispering. “Did your family send you to see the last of us dead?”

Ariane found herself lost in his stare, in the bitterness of his words, in the memory of the man he’d been. A man she’d thought she’d loved. A young man whose face had shown only grief and shock when they’d taken him away. No hatred. Not then. Not yet.

Now he hated. Hated her. Hated what she was.

As she looked at him now—chained like a wild beast, his copper eyes unblinking and fixed on hers—Ariane fought desperately for distance. She’d come here for only one reason, to ask one question. To try to understand.

She hadn’t come here to feel her heart pound and her breath come short. What she felt was not what she had prepared herself to feel.

Fear, yes. Pain at old memories.

But there should have been hatred instead of pity, contempt instead of fascination.

The things a sixteen-year-old girl had felt for a forbidden love should have been long dead, buried with her innocent brother.

Ariane swallowed and met his stare. This was a duel, no more—a duel of wills, of minds. So he hated her. What he felt mattered not at all.

Deliberately she moved away from the table, stopped a bare meter away from him, nothing between them but his bonds.

“My family didn’t send me here,” she said quietly. “I came to ask only one question.” She swallowed again. “Why?”

Rook leaned back as far as his shackles would allow, and Ariane’s eyes were drawn to the dark vee of his broad chest where the stained and ragged work shirt was open nearly to the waist. “Why?” he echoed.

“Why did you kill my brother?”

His closed expression shifted, revealing a flicker of uncertainty, as if her question had truly startled him. “What does it matter, Lady Ariane?” he grated. “Eight years ago it didn’t matter.”

Closing her eyes, Ariane felt her heart stop and start again with painful slowness.

He didn’t deny it.

“I thought—” she began, and caught herself. “It matters.” She opened her eyes again. “He wanted to help your people. He believed you were worth helping. Even if you hated—the rest of us—you had nothing to gain by killing him. Nothing.”

Eight years dissolved in a wave of vivid memory. “All I know is that I have to keep you safe, Lady Ariane. You and your brother. Your lives are worth more to the Patriarch than all of my people combined.”

His words. Words she had never quite forgotten. A contradiction of everything that had come after.

Suddenly she was sixteen years old again, betrayed and grief stricken and lost. She struggled with her weakness, met his gaze and held it as she had done on that terrible day.

He looked away. Deep, unutterable weariness crossed his face, harsh lines relaxing into despair. “I had nothing to gain,” he repeated softly. “Nothing.”

Ariane balled her hands into fists, welcoming the sharp pain as her nails cut the skin of her palms.

“Tell me,” she demanded, drawn closer to him almost against her will. She could smell his sweat and some other scent too subtle to name. “Do you still deny that you killed him?”

Astonishment registered on his face, there and gone in an instant. He looked up at her again and his eyes searched hers, swept over her as if seeing her for the first time. The bronzed skin of his bare arms shuddered, a trapped animal’s shivering.

“You were there,” he said, his voice almost inaudible. “You testified against me.”

Ariane fought a sudden wave of nausea, remembering. “Do you deny it?” she repeated.

The silence between them became oppressive. Rook’s face changed again, hardening, mocking her vain and childish hopes. He is not innocent, she told herself bitterly. The evidence was too strong. Wynn was right. I was only a child….

Rook’s hands worked, clenching and unclenching below the manacles. “Would it change anything if I did?” he said harshly.

She wanted to hit him, wipe that bitter contempt from his face. “Was it an accident?” she persisted, driven by something in herself she didn’t understand. “Pour l’amour de Dieu, if you were innocent—”

“Innocent?” He made a sound deep in his throat, a strangled laugh. “No, Lady Ariane. Not anymore.” Hard calculation moved behind his eyes. “Are you?”

Control snapped. Her hand came up, intending to strike, but she caught herself in midswing. Her palm slapped the warm damp skin of his shoulder.

She staggered as white light flared behind her eyes, clutched at his arm to keep from falling. Violent colors, images, sounds stripped sanity from the world.

Like that terrible night eight years ago, when she had felt and seen and heard too many things she did not understand.

He could not touch her, and yet he did—as if invisible bonds like those that confined him had coiled up at his command to snare her hands and feet. Bonds that tightened in a stranglehold, severing her connection to all she knew. And in a chaos of sensation and emotion not her own, Rook’s eyes drew her in to the center of the storm.

“It was no accident,” she heard him say. And she saw Jacques’s death again, watched it happen, knowing she could do nothing to stop it. No accident, no accident, no accident…

Violently she pushed herself away, breaking contact, and the floor rose up to meet her. She fought to draw air back into her lungs; a scarred face hovered somewhere over her, drained of color. Go away, she told it, and it vanished, along with the memories she could not bear.

“Lady Ariane!” Gentle hands touched her, helped her up. “Are you all right?” Other voices followed, barking commands; she let Hudson guide her from the stifling room.

She leaned against the corridor wall until the sickness receded. Hudson put a glass in her hands. She gulped down the lukewarm water and drew a shaking hand across her mouth.

“Lady Ariane—are you sure you’re all right? They took him away. If he hurt you—” Hudson’s anxious words spun out into a meaningless drone. When the deputy warden came to question her, they told her she had fainted. The last thing she could remember was Rook’s scarred, bitter face and his mocking denial of innocence.

It was no accident.

She wanted to run, to escape this place that held him, but they would not let her leave. “Morning,” they told her. “Too dangerous at night.” And so she lay in the narrow bunk in the small gray room they appropriated for her use, and listened to the wild night cries that the thick barrack walls could not completely banish, and let go of the last forbidden hope.

#

Rook paced his cell, three strides up and three back, using the mindless, familiar rhythm to bring his thoughts back under control.

He had never expected to see her again. He had never believed that it could all come back with such staggering force to reawaken emotions only the old Rook Galloway might have recognized.

One by one his companions had died, until only he remained. And he’d survived—survived because it was the nature of his kind, and because Elder Fox had asked it of him.

Even Fox was gone now. Rook had learned the old, almost forgotten secrets from Fox and concealed the knowledge he’d been given, believing then that he might use it one day. To escape.

Like a captive shadowcat he’d struggled, clung to the fragments of hope, driven by anger. Anger had kept him alive, fighting fate, refusing to surrender. But after eight years despair had entered his soul at last and eaten at his resolve like some alien, insidious disease for which there was no cure. He had learned to accept, to cast off emotion. There had been a kind of peace in the acknowledgment of despair. Peace in his utter aloneness.

Until she had come to Tantalus and shattered that peace.

The guards had taken him to the interrogation room and he’d seen her face. High walls had crumbled in an instant, and the man hidden within them had lain exposed. Weak, cringing, thrust again into a holocaust of bitter memory.

He’d wanted to run, but it was too late. He had learned to feel again.

Rage, sorrow, yearning.

Hope.

And hatred. Hatred for the woman who had come to torment him, and for all she was. He tasted that hatred, turned it over in his mind, greeted it like an old friend. Hatred was an anchor in the maelstrom of emotion. He could find strength in it, a new means for survival. A new purpose.

Ariane Burke-Marchand. She had given him that purpose.

Rook closed his eyes and let the images play out in darkness. He thought of the woman, and of the child she had been—the one person who symbolized the tragedy that had befallen his people and condemned him to hell.

He remembered the smudged, anxious face of a girl just old enough to believe herself a woman; a tangle of dirty hair, wide dark eyes. He remembered her angry curses, her loyalty to a brother she loved. He remembered the way she had looked at him in the end: accusation and horror, a gaze stripped of innocence.

He remembered her at the trial, when she had spoken softly of what she had seen when her brother died. She’d only been a tiny part of it, of the deliberate web of lies spun to trap his people. Conspiracy, they’d called it—a conspiracy of the educated Kalians to turn on their patrons, careful plans of revolt and blackmail and violence exposed just in time.

But he had never hated her, even when her carefully guided words had helped condemn her. He could not hate a child.

But she was no longer a child. She was Marchand. And she had come to Tantalus with her doubts and her questions eight years too late.

Rook worked his hands, still feeling the shackles. He had wanted to touch her. He had wanted it desperately, without comprehension, even as he’d hated her and everything she was.

And when she’d touched him– He shuddered, remembering light and sensation and denial. Something had happened between them, something inexplicable. In a single moment, he’d relived the tragedy that linked them, Marchand and Kalian, and he’d wanted to make her feel it, force her to understand, to know the truth. He had wanted her . . . .

The clear shielding of his cell rang with a sudden blow, and Rook pivoted to face the guards who stood on the other side.

“Hey, Galloway!” the older one said, rapping his stinger against the shield a second time. “Missing your girlfriend? Hear she came all the way from Espérance just to see you!” He snickered. “Who’d have thought you were worth it, eh? Such a nice little armful she is. Too bad your hands were tied, eh?” Both guards laughed, and the younger one made suggestive movements with his hands.

Black rage shivered through Rook, more familiar this time. Almost sweet. A day ago he would have been indifferent to their jibes. Now he held himself in control, silent and still, staring — until they dropped their eyes with scowls and curses.

“The warden wants to see you, Galloway,” the younger guard said at last. He fingered his stinger. “You gonna give us any trouble?”

Rook looked away to conceal his sudden, fierce joy. Trouble. Let them believe he was still the broken savage, a dull creature good only for backbreaking labor, lost in his own world. Let them believe until it was too late.

The guards raised the shielding, and he let them push him into the corridor while he listened to the Tantalan night.

He could almost feel her, somewhere near, just out of reach. He went quietly with the guards and thought of Ariane Burke-Marchand.

She had resurrected him. She had made him feel again. Unwittingly, she had restored his purpose and given him the means to act.

She was his link to the past, and his key to the future.

Today Rook Galloway had been reborn.