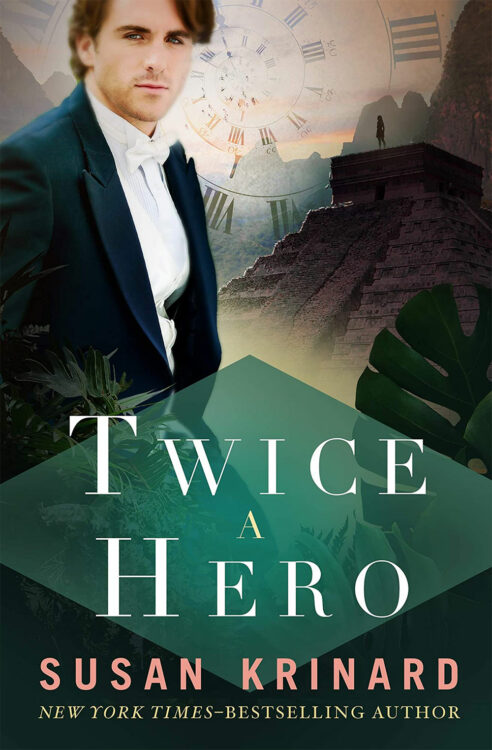

Twice a Hero

A time-travel romance “with all the grace and sensuality readers have come to expect from” the New York Times–bestselling author of Star-Crossed (Library Journal).

To lift a family curse, MacKenzie Sinclair heads to the Guatemalan jungle to return an amulet her great-great grandfather, Perry Sinclair, took from a Mayan temple. On that same expedition, his partner, Liam O’Shea, disappeared—possibly betrayed or killed by Perry—which started the Sinclair family’s string of bad luck.

Once at the ruins of the ancient city of Tikal, Mac is sent back in time to 1884—and into the life of Liam O’Shea. Together with the headstrong, honorable, and disarmingly handsome adventurer, Mac has a chance to turn the tide of history—and the fortunes of her own heart.

The book has been published previously with Bantam in 1997.

Read an Excerpt

As the excerpt begins, Mac has just found a guide to lead her deeper in to the jungle in search of the legacy of Liam O’Shea . . .

After almost an hour of walking, Mac was beginning to feel rebellious.

Homer, are you watching? This had better be worth it.

It was. One moment she was floundering in her guide’s wake, and the next she walked into a tiny clearing and came face to face with a vine-covered ruin.

The place bore little resemblance to the great ruins of central Tikal. A thousand years ago it had been part of the great Maya city-state, which had sprawled over fifty square miles. Now it was a crumbling collection of unexcavated minor buildings. Such places dotted the Petén, Guatemala’s lowland jungle, a dime a dozen.

But it had a very peculiar effect on Mac. She stopped and caught her breath, mesmerized. She eased out of her backpack and crouched where she was, taking it all in.

Wild. Ancient. Untamed in a way Tikal proper no longer was. And Mac’s heart came alive as it hadn’t done in the spectacular but well-trodden Maya city.

This was what Tikal had been like when Perry and Liam O’Shea had come to the Petén. This must have been what they felt when they made a discovery, knew they could be the first Americans to see what the jungle had hidden.

This was exactly the place to enact her little ceremony of contrition for Sinclair transgressions. This could even be the place where they found the pendant. Another crazy thought that no longer felt quite so crazy. She wiped sweaty palms on her khakis and reached for the piece of carved stone that hung around her neck.

It was warm. Hell, everything was warm here—but she’d expected stone, at least, to be cool.

She released the pendant and stood. “I never caught your name,” she said to the guide, who’d moved off somewhere behind her. “Do you know what this place is called?”

Overhead a macaw shrieked. Mac turned around. The boy wasn’t there. She pivoted. No sign of him at all.

“Great,” she said. “Hello? Hola?”

A mosquito whined next to her ear. She waved it away and started back down the path the boy had cut. Not a single swaying leaf hinted that he’d been there any time recently. “O . . . kay.” She planted her hands on her hips and looked up through the forest canopy at the sky. Still light for several more hours, anyway. At least the kid had made her a trail to return.

She turned to the ruins once more. Here she was, living an adventure—alone, in the jungle, with a piece of three- dimensional history smack-dab in front of her. Homer would be proud.

And Liam O’Shea was waiting.

The thought sobered her. She walked toward the ruins, picking her way over rubble and low brush. She crouched to examine massive, fallen stone steles, patterned by Maya glyphs. Beyond was the first of several buildings, blackened by time, covered by moss and lichen and every kind of tropical vegetation that could gain a foothold.

She walked around the nearest building. From the rear she could see something that hadn’t been completely visible before — another, larger structure, and the gaping black maw of an entrance. Temple or palace; she wasn’t enough of a Maya scholar to know what the building might be. The narrow-stepped stairway leading to the top of its platform did not rise very high as such buildings went. The rear of the building was butted up against a limestone ridge, and jungle growth had nearly obscured the roof and walls.

The black square of the entrance seemed to lead right into the steep hillside. She knew that the Maya had considered their temples to be artificial sacred caves, their portals gates to the world of the gods. The doorway drew her with its mysterious promise of secrets hidden from daylight.

On impulse she crossed the hundred yards to the building and paused at the entrance. Cooler air brushed her cheeks. She leaned against the stones and peered into darkness. There was no hint of light inside, but obviously the way had been cleared by someone, and not too long ago. That meant anything of value within would long since have been looted.

But there was a feeling deep in her gut that her ritual must be enacted here, a place held sacred so long ago. She had to go in.

Mac squared her shoulders and clasped her pendant. It was no longer merely warm, but almost hot to the touch. The stone must have remarkable properties of heat transference if it could take on her body’s temperature so quickly and hold it so well. She considered removing the pendant to see if it would cool off again, but somehow she felt the need to keep it where it was until she was ready to consign it back to the earth.

Superstition, she thought, but what if it was? No one was around to know she’d taken the first dangerous step from solid reality into a realm of uncertain fantasy.

The next step was physical. She dug out her flashlight, switched it on, and started into the entrance. She didn’t expect to go very far. There would probably be a series of smallish rooms, all dark and damp, where once priests or lords had carried out sacred ceremonies.

She shivered a little in spite of the heat and swung the flashlight beam back and forth, surprised that she still hadn’t reached the rear of the building, or even a partition. Instead the walls came closer together the farther inward she advanced, until she was in a long, narrow tunnel.

By now she had to be under the limestone ridge itself. She stopped to run the flashlight beam behind her, along the uneven floor and up and down the walls. Plain and bare, as she’d suspected. Disappointment washed over her.

What did you expect? There wasn’t likely to be some fantastic altar conveniently available for her ceremony. Still, the urge to keep going was too strong to resist.

“I know what you’d say, Homer. Get to the end before you turn back.” At least the flies and mosquitoes hadn’t followed her. She focused the flashlight dead ahead and kept walking. And walking. Something was definitely crazy here. She glanced at her watch, grateful for the illuminated dial. Ten minutes she’d been walking, albeit at a very plodding pace.

This was crazy. If she didn’t hit a wall or something in the next few yards, she was going back.

At the requisite few yards, an instant before she turned away, her flashlight beam splashed against a wall. Stone rose in front of her, solid and implacable.

And not plain. No, definitely not plain. The entire surface was crowded with Maya glyphs. Undefaced, unchipped, uncracked, as if time itself had stood still within this strange hallway. There was no other word for it than awesome. She didn’t have an expert’s ability to decipher the ancient symbols, but she recognized the glyphs that represented the passage of time, and dates, and the vaster measurements by which the Maya had calculated the march of eons. They had been obsessed with time, those ancient ones—time far before their first civilization, and time to come long after they had vanished.

She stroked the light down the surface of the wall to the more conventional relief carved under the rows of glyphs. It showed a man—a lord—in full feathered Maya regalia. But though everything else in the scene was perfectly depicted, there was something wrong with the man’s figure. It seemed to be cleanly cut off halfway through the body. He was shown walking purposefully, in profile, directly into a wall. And the wall bisected his body, as if half of him had melted into it. She’d never seen anything like that before, not in any book or exhibit or in Tikal itself.

She moved cautiously forward again; her toe brushed something that rattled and rolled under her foot. Instinctively she aimed the flashlight down, expecting rubble, though the floor here was clean of it.

Instead, she found bones.

Human bones.

Mac had never been the flighty sort. She didn’t jump back, or scream. That kind of stereotypical female behavior had been left out of the mold that had shaped her sturdy, too-rangy body. So she only looked. That the bones had been here for some time was evident by their condition. There was not a scrap of flesh left on any of them, and only traces of rotted fabric that must once have been clothing.

She followed the loose trail of leg bones to where the torso had collapsed close to the wall. Somehow the rib cage, vertebrae, clavicles and skull had fallen in almost a straight line. Or perhaps someone had laid them out there.

Morbid curiosity brought her closer. The bones were large; masculine, she guessed. Someone who’d been tall, well built. She winced at the grinning skull. Why did people refer to them as grinning, when they were all that remained of a once-vital life?

She gripped her pendant again, comforted by its inexplicable heat. Who were you? A guide like that boy who led me here? A tourist who made a fatal mistake in the jungle?

Mac found herself rapidly losing her enthusiasm for the adventure. Wasn’t she here to mourn the death of someone who’d died in a place just like this? Whose bones might be lying, untended, where no one would ever find them —

Her thoughts dwindled to incoherence as the beam of her flashlight came to rest at the base of the skull. Something lay among the vertebrae — something slightly darker, more regular. Familiar. A stone chip, drilled through the top, the remains of a rotted leather cord twisted through it.

Mac dropped into a crouch and leaned closer, careful not to disturb the bones.

And she knew. She knew before she saw the chip close up, before she dared to touch it and lift it to her eyes. She knew exactly how it would match her own pendant, how it would be the other half of a whole once broken in two. When she pressed the irregular edge of the chip against that of her own, it fit like a hand in a glove.

“Oh, God,” she said hoarsely. “It can’t be. The world doesn’t work this way.”

No. Life didn’t do things like this—make it so easy, so convenient, giving you a guide to lead you right to where he’d died, so close to Tikal, in a place a hundred others would have seen before you. This could not be Liam O’Shea.

But she knew it was. She knew with a certainty beyond reason. “Liam,” she said, tasting the name. This was all that remained of that handsome, arrogant, alive young man she’d seen in the photo. She’d done what Homer had asked, and more. She’d found Perry’s partner. The man he’d murdered.

She felt as if she’d been kicked hard in the solar plexus. Her knees buckled. There, face to face with hard reality, she bent her head and mourned. And, in her hands, the two halves of the stone chip burned and burned.

The brief ceremony she’d planned was no longer something simple and far away. It was as real and inescapable as Liam’s bones.

What now, Homer? Do I bury him along with the pendant, and hope that will be enough? But she knew it wouldn’t be, somehow. Even apologies would never be enough. Now she understood the weight of guilt Homer had felt near the end, as if Peregrine Sinclair’s evil act had come to rest on her own shoulders. And only she could set it right.

Mac rose shakily. It was so damned hard to think of Liam O’Shea as this pile of bones. She didn’t take out the photo, though she wanted to. As if that could bring him to life again.

She forced herself to turn back to the wall. She needed to clear her mind. There was something regular and soothing about the glyphs and ritual figures carved into the limestone surface. Repetitive and patterned, yet elegant and profound. She followed each line of glyphs from right to left and back again, trying not to think of Liam O’Shea.

Had he been afraid when he died? Had he cried out for someone to care, someone to hold his hand as Mac had done with Homer? Had he cursed the Sinclairs with his dying breath?

She laughed a little and leaned her folded hands against the wall, one stone chip still nested in each palm. “I wish I could undo it, Homer,” she said. “His death, the curse, everything. Maybe you’d still be alive. Maybe Dad, and Mom—oh, this is insane. But if I could go back . . .”

In her right hand, Perry’s stone chip flared like a burning brand. In her left, Liam’s did the same. A wave of overwhelming nausea caught her by the throat and twisted her innards, propelling her away from the wall. Her fingers spasmed helplessly around the pendants even as they seared her flesh.

A black stab of pain shot into her skull, and she knew she was going to faint. She flailed blindly for the wall again, catching the brim of her cap and knocking it from her head. Her fists struck something solid, and the impact drove the broken edges of the pendants into her palms with enough force to pierce the skin.

The slow welling of blood startled her into a moment of lucidity. She opened her hands. At the precise moment the pendants dropped to the ground, the wall she was leaning on vanished.

She fell. It seemed she traveled toward the ground for a much longer time than distance or gravity could account for. The nausea redoubled, accompanied by a pounding in her skull that drove out anything resembling a coherent thought. When she hit the floor it was as if she landed on something soft rather than unevenly laid stone. A moment later she felt the impact and rolled into a compact ball, waiting for the temple to crash down on top of her.

It didn’t. She straightened carefully. The sickness and pain were miraculously gone, but she was in total darkness. Her flashlight had been knocked from her hand; she couldn’t tell where the tunnel walls were, or how far she’d fallen. Logic dictated that it couldn’t have been more than a few feet. But what in hell had happened to the glyph wall?

“Hidden trap doorways?” she murmured, getting to hands and knees. “Never heard of those, either.” She kept up a steady stream of talk, listening to her one-sided conversation echo back from unseen walls, reminding herself that she’d never really been afraid of the dark. She’d grown up in a big echoing house with a thousand rooms full of mysterious and often scary objects—or so it had felt to a child.

She checked her backpack by feel; okay. Her body was still in one piece. Watch still functioning—she’d been in this place for almost an hour. Next thing was to find the flashlight—and Homer’s cap, which she’d been clumsy enough to knock from her own head.

As for the pendants—they, too, were gone, and the ceremony of repentance had yet to be performed.

She groped along the floor, scraping her hands on rough edges where blocks met unevenly. She felt up and to the side and connected with a wall—flat and damp and uncarved. She oriented herself by that and crawled what she thought was the way she’d come. No carved glyph-wall met her searching fingers. But the flashlight rolled against her knee, and she grabbed it with a gasp of relief. A quick test showed that it was still working, though it had been switched off sometime in the fall.

She swept the beam ahead of her, pushing to her feet. Sure enough, the walls were there on either side of her, exactly the same as they’d been before. But the glyph-wall wasn’t there, and neither were Liam’s bones or the pendants. Either she’d gone flying yards into the tunnel, or she’d become totally disoriented in the darkness.

Panic was not a familiar emotion, or one she had any desire to become better acquainted with. Okay—the glyph-wall had to be either one way or the other. Once she bumped into it, she’d know where she was.

She played a quick mental game and chose one of the directions. After a minute she knew it couldn’t be the right one. She turned around and marched back the other way with a speed that was just a bit reckless in the dark.

When she hit the next firm, hard surface it was definitely not a wall. Her hands came up to steady herself and pressed against warm, damp fabric covering equally warm and unmistakable contours. Hard, sculpted contours. Masculine. Definitely masculine. And they didn’t belong to the skinny boy who’d guided her to this place.

The smell of sweat and green and earth and man filled her nostrils. Deep, harsh breathing gusted past her ear. She dropped her hands and backed away, holding the flashlight low so as not to blind him.

“Am I glad I ran into you,” she said. “I’ve been wandering inside this tunnel for what feels like hours.” She heard the rapid patter of her own words and realized how nervous she sounded. She had absolutely no idea who this guy could be. “I . . . seem to have gotten myself turned around. I thought I was alone here.”

He gave a low grunt. In the faint illumination radiating from the flashlight, all she could see of him was solid height, light- colored clothing and a glitter of eyes.

“What are you doing in here, boy?”

She stiffened, every other concern momentarily wiped clean from her mind. The lapse was brief. How many times had this happened to her during childhood? It wasn’t such an easy mistake to make now that she’d grown, but in all fairness she knew she contributed to the problem because of her preference for loose, comfortable, practical clothing.

This guy couldn’t see her clothing, or much of the rest of her. She knew her voice was husky and low, a little rough now with nervousness. That must account for it. She made herself relax and decided that perhaps it wasn’t such a bad idea to let him think she was male. At least for the time being.

A hard, very large hand caught her arm. “You’re American. How did you get here?”

She held her arm very still in his grasp. “Yeah, I’m American.” As if it’s any of your business, buster. “I came to see the ruins. I walked. I didn’t know this tunnel went so far.”

The man felt up the length of her arm. “Just how young are you? Where’s your party?” His voice was deep, with an edge of roughness—eminently masculine, like his grip and size. She began to feel more than a little annoyed.

“Party? Did I miss the celebration?” she quipped.

He gave a bark of laughter, but in the dim glow she could see his eyes narrow. “Who did you come with? I didn’t see anyone else in the jungle. The Indians said no one’s been here for months.”

No one here for months? She snorted and pulled her arm free. “Look, friend, I don’t know who you are or where you’ve been, but if you go a mile or so south of here you’ll run right into Tikal. Which is where I intend to be very shortly.” The minute I’ve finished what I came here to do, that is.

“Tikal,” he repeated. “I would have known if anyone else was here.”

Great. She’d had just the luck to run into a lunatic in a very dark tunnel. She backed away. “Whatever you say. If you don’t mind, I have business to take care of.”

She calculated how best to slip around him and had gone a few yards when he reappeared beside her. His footfalls were eerily soundless; the hair stood up on her neck.

“I’ll join you, lad. My lantern broke, and I’ll need your light.”

Great. “Well, uh, that would be fine except I have something to do before I leave—”

“Nonsense. This is no place for a child.” His hand fastened around her arm again before she could dodge out of the way. The masculine scent of him, as primal as the jungle itself, nearly overpowered her. His strength was irresistible, though Mac had never been weak. Fighting him didn’t seem like such a good idea just now.

“You can take me to your camp when we’re out of here,” he said, steering her along. “I have supplies to replenish, and I want to see who arrived without my knowing about it.”

He sounded disgruntled, she thought. What did he expect— having the entire jungle and its contents to himself? He’d be plenty annoyed when he saw all the tourists at Tikal.

“I can show you the trail back to Tikal,” she said. And you can bet we’ll part company the minute I get the chance.

“Will you, then?” he said, and gave an inelegant snort. “I’ll appreciate the help.”

She thought better of saying anything more at that point, though she was constantly aware of his presence at her side. He was big and well-built, of that much she was certain. If he were crazy, she’d have a hard time throwing him off. Maybe he was some kind of hermit who’d come here to live in solitude. The Petén might be a good place for that, if you didn’t mind rain, mud, mosquitoes and flies and didn’t stick too close to the tourist traps at Tikal.

Maybe this guy had been a hermit too long.

Now you’re really letting your imagination run away with you. . . .

“There,” the man said suddenly. “The entrance.”

And sure enough, there was a faint patina of illumination along the tunnel walls. Mac heard a faint hiss that grew louder as the brightness increased.

Rain. Not merely a drizzle, but torrents and buckets of rain, sheeting across the bright square that defined the exit. Great. She’d deliberately come to Tikal during the August dry period, but apparently she’d cut it too fine. She’d be drenched, and the trail back to Tikal would be a soup of mud.

Her unwanted companion showed no surprise at the downpour. Before she could turn to examine him in the light, he said something unintelligible and pushed past her.

Mac stopped just inside the shelter of the tunnel. The man had plunged right out into the rain and stood with his back to her, hands on hips and head flung back in defiance of the weather. The rain made short work of plastering his shirt and pants flush to his body, confirming what Mac had already guessed by touch alone.

He was tall. Over six feet, she guessed, and not in the least skinny. Broad shoulders, taut back, firm buttocks. Wavy pale brown hair, just brushing the back of his collar, darkened to a deeper hue as the rain slicked it down. He was very impressive, even from a rear view. Perhaps even especially from a rear view. . . .

Mac felt a jolt of chagrin at the direction of her thoughts. She’d never really let herself admire men in a purely physical sense, not since that one disastrous and very brief relationship in college.

But now she looked. Damn it, why not? She was out in a comparatively safe jungle where no one knew her, where all bets were off and magic waited just behind the next tree. Maybe that was it, why she studied the man with such fascination. He was . . .

Yes. He was part of the magic. He was the opposite of the grim reality of Liam’s bones in the tunnel, or curses that echoed down the generations. He was the incarnation of adventure itself, like an ancient idol brought to life. He was an integral part of his surroundings—the ruins, the jungle, even the rain and mud. He owned the place. He belonged here.

Mac let herself share in that belonging, experience the feeling of being suspended in time and space, free for the moment of any lingering guilt over a past she’d had no part of. Slowly she stepped out into the rain. It baptized her with fierce joy, making a close cap of her hair and soaking her clothing in a matter of seconds, bathing face and arms and legs. She felt water trickle under her shirt and between her breasts. A tingle of awareness tightened her nipples.

Primal. Primeval. This was nature in its glory, and somehow it passed a little of that glory on to her. She wasn’t plain, ordinary Mac anymore. She was a goddess of the forest, a dauntless heroine ready to meet any challenge. . . .

“I’ll be damned. You’re a woman!”

The man’s deep, husky voice snapped Mac out of her reverie. He had turned around; a retort was already on her lips before she got a good glimpse of his features.

“Gee, thanks for clearing that up. I—” She found herself gazing into eyes that gave new meaning to the hackneyed phrase “steely gray”. For a moment all she could do was stand in gaping silence as the man examined her with insulting thoroughness.

“I don’t believe it,” he said. “What the hell are you doing here?”

But she wasn’t really listening. She didn’t have time to resent his critical tone or his arrogant questions or the fact that he was acting just as she’d expect a typical male to act when confronted with the unimpressive MacKenzie Rose Sinclair.

All she could hear was the pounding of her own heart and the startled rasp of her own breathing. And all she could see was his strong and powerfully masculine face.

A face she recognized. A face she’d first seen months ago. A face she’d been carrying around in her backpack ever since she’d left the San Francisco International Airport for the wilds of Central America.

The man was the spitting image of Liam O’Shea.